Discussion about the Roman liturgy varies in Catholic circles. For most liturgically interested Catholics the debate is between the "EF" and the "OF," or how the "reverence" of the "EF" might improve the "OF," or even how an amalgamated rite could be fostered. Others, the SSPX/FSSP type traditionalists who attend churches not staffed by diocesan priests, contrast the "theology" of the "Traditional Latin Mass" with that of the Mass of Paul VI, praising the emphasis on sacrifice in the former and criticizing the excessive focus on the meal elements of the Eucharist in the latter. Even more radical traditionalists focus on the "pre-1955" Missal, which is most typical editions published, versus the 1962 rite; people in this crowd inevitably dwell on Annibale Bugnini's role in crafting Pius XII's dodgy new Holy Week rites, in some sense inferior to those in the Pauline Missal (regardless of what one may think of the

Ordo Missae in the Pauline books). Something neglected in all these discussions is the liturgical year itself and its contributions.

It is safe to say that the older rites, 1962 or 1474, have a more involved liturgical year, with more vigils, the ember days, and richer texts in the Office and at Mass for Advent and Lent than the modern books. But what of another long neglected aspect of the kalendar: octaves.

Octaves merit little attention these day, aside from discussion of the Octave of Pentecost in the 1962 rite, because both the Pauline kalendar and the Johannine kalendar have so few, two and three respectively. Prior to 1955 octaves occupied a very prominent place in the liturgical year of the Roman Church. For well over a thousand years the Church set aside eight day periods for the observation and re-visitation of the mysteries and salvific action of God in His works and in His saints. Most recently we would have finished the octave of All Saints, one of the most recent octaves, on November 8th. So what is an octave and what does it matter?

"In the beginning God created heaven and earth," thus begins the Holy Scripture in the Book of Genesis. On the first day gave began creation, a gradual effort in which He fashioned everything for six days and then, on the seventh day, left it as it was. In light of the Resurrection, which occurred the day after the day of the rest, the Christian sees the eighth day as the beginning of a new creation, which is, in effect, a renewal and a re-vivification of the old creation. As Christ rose from the dead with the same body, but glorified and transformed (Philippians 3:21), so the Christian will at the end of time at the Last Judgment. But this process is not so removed from our current time and current needs.

In Greek, so the Byzantines tell me, the phrase the "Kingdom of God is at hand" (Mark 1:14, Matthew 3:2, Matthew 10:7) does not mean that the end of the world is immanent, but that the Kingdom of God, which was formerly inaccessible, is now immediately accessible, although in a less tangible form than what will be found at the end of time. Christianity, which is a fundamentally liturgical religion, is a fundamentally eschatological religion. What will happen in the end happens to the Christian now. He is joined to events that have happened, such as the Resurrection or the descent of the Holy Spirit at Pentecost, and to things yet to come. In short, the Christian's baptism binds him to mysteries of God that exist outside of time and which will transform the world at the end, at the eschaton. Our participation in the eschaton through baptism on earth necessitates our observation of God's creation and recreation, of the Son's Life and Resurrection in this time. This is what was foreshadowed in the Old Testament for us and what was done in the Roman liturgy in a very complete way until 1955, and in a very reduced way after 1955.

In chapter 23 of Leviticus the Lord establishes the Day of Atonement, the beginning of a seven day cycle of sacrifices for the sins of the people called the "Feast of Tabernacles" or the "Feast of Booths"—called such because the Jews would build booths out of palm branches in which they would live during those seven days. On the eighth day the offering of sacrifices was renewed with greater solemnity (Leviticus 23:36), forming the first octave, a foreshadowing of what was to come on the eighth day many years later. Not only did the Feast of Tabernacles begin on the Sabbath, a day of rest, and end on the Sabbath, a day of rest, but God prohibited servile work on the days between (Leviticus 23:35), extending the penance—or celebration for the Christian—for eighth days.

|

| source: modeoflife.wordpress.com |

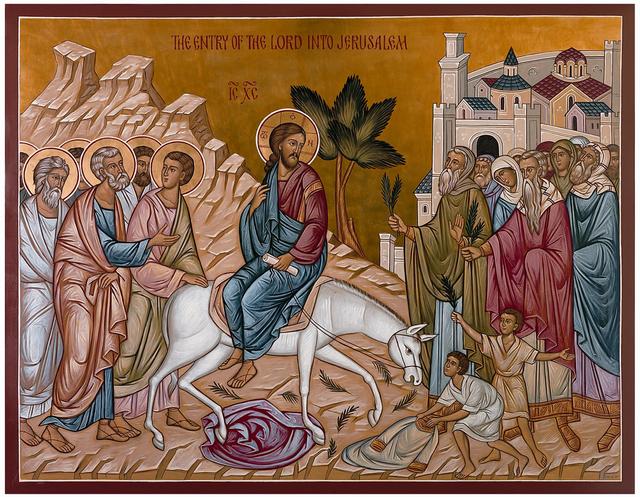

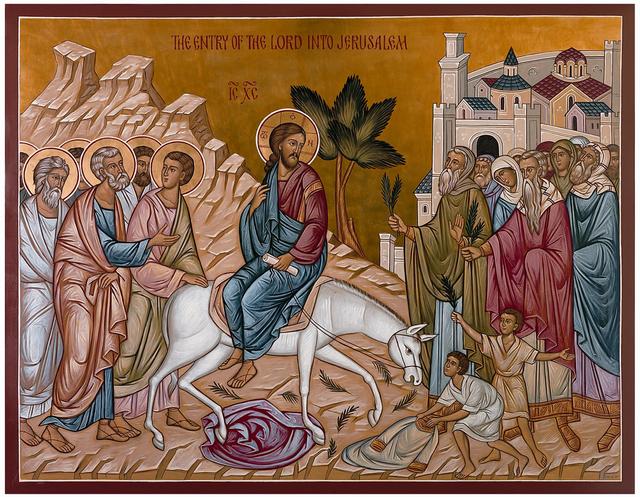

On Palm Sunday, to my view, Christ began the first Christian octave. The Jews often enthroned their king during the Feast of Tabernacles (Danielou Bible and the Liturgy 335). On this day the Jews sang psalm 117, a psalm the Byzantine rite still sings during Communion and which the Roman Mass utilizes on Pascha, which includes that renown word "Hosanna." What did the Jews sing on Palm Sunday? "Hosanna to the Son of David" (Matthew 21:9). What were they doing? Holding branches of palms, as they would during the Feast of Tabernacles (Ibid 21:8). The narrative draws a clear parallel between the coronation of the king and the entrance of Jesus into Jerusalem. The inhabitants were enthroning Him as their new king, Why was the Feast of Tabernacles observed? To remind the Jews of their deliverance. Why did Christ enter Jerusalem? To observe the Passover and to fulfill the true deliverance, deliverance from sin and death. He would "rest" on the seventh day and rise again, in a renewed body, on the eighth day.

In some sense, although not strictly part of the liturgy, the period from Palm Sunday to Low Sunday forms consecutive octaves, the first ending with the new Creation and the second concluding with a greater clarity and invigorated spirit which only adds to that new Creation (Christ giving the Holy Spirit and power to forgive sins to His Apostles in the Upper Room).

As God made the Jewish people do penance and offer sacrifice for their sins for seven days, creation lasted seven days, and as they redoubled their efforts on the eighth, He renewed creation on the eighth in His Son's Resurrection from the dead. This process of creation, exploration, growth, and renewal is at the heart of Christ's work and, as it exists in time, makes His work accessible to us on earth, for us living in the eschaton terrestrially. The Church observes octaves—and observed even more—precisely for this point.

Many readers will know that Pascha, Christmas, and, in the older rites, Pentecost mandate octave length celebrations. Formerly well over a dozen occasions did so. Among them we see great evidence for the above analysis. St. John the Baptist's Nativity took an octave, the only Saint other than Our Lady whose birthday rather than death day is observed as a feast, suggesting that St. John was born without sin. If so, his own conception, birth, and life are a great act of God's restoration of human nature into its holier form. The same can be said of the Octave of All Saints.

|

| source: glory2godforallthings.com |

A more startling example might be Epiphany, a feast of greater importance than Christmas if we are to be theologically honest with ourselves. Why was Epiphany observed as an octave until the last years of Pius XII? What renewal or improvement did it offer on the eighth day? "Epiphany" literally means a "showing" of something, in this case the showing of God in the flesh to Gentiles, a revelation that this Child's work would benefit all men, not exclusively Jewish people. On the eighth day, the octave day of Epiphany, an even greater revelation is shown to us, that of the Holy Trinity. The octave day of Epiphany is the Baptism of the Lord in the Jordan by St. John, wherein the Holy Spirit descended upon the Son and the Father said He was "well pleased" with the Son (John 1:29-34). This was the first direct revelation of the Holy Trinity to mankind, an even greater, but not segregated, revelation than that of Epiphany.

Octaves did not regularly appear during Paschaltide (except for the 19th century feast of St. Joseph), owing to the already Paschal nature of the season, and of course not during Lent. Instead the Church of Rome gave her faithful octaves to observe throughout the rest of the year, particularly during the time after Pentecost, during which the faithful might always recall how the Saints were in themselves new creations (Ss. Peter & Paul, John the Baptist, Lawrence of Rome, the Assumption of Our Lady, the Nativity of Our Lady, and All Saints all occur during the "green" Sunday season).

Yet does not the evidence oppose my eschatological hypothesis? Were these octaves so important and were the eighth day so relevant in liturgical theology surely the Church of Rome would have devised unique Masses for the days within the octaves, as she did for Pascha and Pentecost, rather than repeat the festive Mass again and again. Not so! In older times, outside of monasteries and collegiate churches, Mass would only be observed on Holy Days and Sundays. The repetition of Masses is the consequence of filling in the days between the feast and the nearest Sunday or Sunday and the octave day. Where octaves are truly to be observed is in the Divine Office. The lessons at Mattins would progress through didactic material germane to the mystery at hand for eight days and the antiphons repeated at the major hours would do much the same. Gregory DiPippo has been doing a fascinating series on the Mattins lessons for the Octave of All Saints in the Roman Curial Breviary which can be read

here. The use of the festive office, with shorter psalms and no penitential prayers as would be found on ferial or simple days, contrasted starkly with the almost brutal daily cycle of prayers found in the ferial psalter. Octaves were clearly a time of joy, a period of living out some holy mystery in the present (although some of this was lost in the 1911 re-distribution of the psalter).

Liturgical octaves observe the eighth day of creation, the renewal of creation in the Resurrection of Christ. They make what is distant to us immanent and accessible as Christ's own salvific work made it immanent and accessible to those who had longed for it and observed it in its type for so long. We, on the other end of salvation history, observe its anti-type, its eschaton. For this reason, and for reasons better stated by those more liturgically learned than myself, we should push to re-introduce octaves into the Roman rite for feasts of saints and for feasts of Our Lord's work.

God bless!

Russell Kirk was a short, stalky man from Michigan who served America in the Second World War and studied philosophy during the years after the War's conclusion. His studies took him to the University of St. Andrews in Scotland, where he was the first American to earn the degree Doctor of Letters there. His dissertation, which initially focused on the thought of Edmund Burke, became a compendium of vignettes on then-forgotten political conservatives from the Anglophonic world, among them John Adams, John Q. Adams, Hamilton, James Fenimore Cooper, John Randolph, Benjamin Disraeli, John Henry Newman, Paul Elmer More, and James FitzJames Stephens. His two principle ideas were that "liberty"—that most American of ideas—is "ordered" by society and not properly a state of moral and political chaos; and that society has a "natural aristocracy" of people who occupy their given places within it. His dissertation was published in 1951 as The Conservative Mind. This was the first of Kirk's books I read in college. Later I found a copy of his Roots of American Order, which traced the intellectual and cultural origins of the United States' political system to ancient Rome, which, after the collapse of Rome, came to England through the missionary efforts of Ss. Gregory the Great and Augustine of Canterbury, was rebuilt during the legal and theological highpoint that was the Middle Ages, solidified itself in an English expression after the 1688 Revolution, and came to North America during the 17th and 18th centuries. His books are nothing groundbreaking to the modern reader, who is well accustomed to the sight of piles upon piles of political buncombe for $15 in the nearest bookshop, department store, or newsstand. During his time though Kirk was the only writer who openly questioned the progressive system put in place by Roosevelt and the force of his words made his case particularly interesting. He eventually teamed up with National Review founders William Buckley and Brent Bozell to spearhead the modern conservative movement in the 1950s, a movement which died in 2001.

Russell Kirk was a short, stalky man from Michigan who served America in the Second World War and studied philosophy during the years after the War's conclusion. His studies took him to the University of St. Andrews in Scotland, where he was the first American to earn the degree Doctor of Letters there. His dissertation, which initially focused on the thought of Edmund Burke, became a compendium of vignettes on then-forgotten political conservatives from the Anglophonic world, among them John Adams, John Q. Adams, Hamilton, James Fenimore Cooper, John Randolph, Benjamin Disraeli, John Henry Newman, Paul Elmer More, and James FitzJames Stephens. His two principle ideas were that "liberty"—that most American of ideas—is "ordered" by society and not properly a state of moral and political chaos; and that society has a "natural aristocracy" of people who occupy their given places within it. His dissertation was published in 1951 as The Conservative Mind. This was the first of Kirk's books I read in college. Later I found a copy of his Roots of American Order, which traced the intellectual and cultural origins of the United States' political system to ancient Rome, which, after the collapse of Rome, came to England through the missionary efforts of Ss. Gregory the Great and Augustine of Canterbury, was rebuilt during the legal and theological highpoint that was the Middle Ages, solidified itself in an English expression after the 1688 Revolution, and came to North America during the 17th and 18th centuries. His books are nothing groundbreaking to the modern reader, who is well accustomed to the sight of piles upon piles of political buncombe for $15 in the nearest bookshop, department store, or newsstand. During his time though Kirk was the only writer who openly questioned the progressive system put in place by Roosevelt and the force of his words made his case particularly interesting. He eventually teamed up with National Review founders William Buckley and Brent Bozell to spearhead the modern conservative movement in the 1950s, a movement which died in 2001. Discussion about the Roman liturgy varies in Catholic circles. For most liturgically interested Catholics the debate is between the "EF" and the "OF," or how the "reverence" of the "EF" might improve the "OF," or even how an amalgamated rite could be fostered. Others, the SSPX/FSSP type traditionalists who attend churches not staffed by diocesan priests, contrast the "theology" of the "Traditional Latin Mass" with that of the Mass of Paul VI, praising the emphasis on sacrifice in the former and criticizing the excessive focus on the meal elements of the Eucharist in the latter. Even more radical traditionalists focus on the "pre-1955" Missal, which is most typical editions published, versus the 1962 rite; people in this crowd inevitably dwell on Annibale Bugnini's role in crafting Pius XII's dodgy new Holy Week rites, in some sense inferior to those in the Pauline Missal (regardless of what one may think of the Ordo Missae in the Pauline books). Something neglected in all these discussions is the liturgical year itself and its contributions.

Discussion about the Roman liturgy varies in Catholic circles. For most liturgically interested Catholics the debate is between the "EF" and the "OF," or how the "reverence" of the "EF" might improve the "OF," or even how an amalgamated rite could be fostered. Others, the SSPX/FSSP type traditionalists who attend churches not staffed by diocesan priests, contrast the "theology" of the "Traditional Latin Mass" with that of the Mass of Paul VI, praising the emphasis on sacrifice in the former and criticizing the excessive focus on the meal elements of the Eucharist in the latter. Even more radical traditionalists focus on the "pre-1955" Missal, which is most typical editions published, versus the 1962 rite; people in this crowd inevitably dwell on Annibale Bugnini's role in crafting Pius XII's dodgy new Holy Week rites, in some sense inferior to those in the Pauline Missal (regardless of what one may think of the Ordo Missae in the Pauline books). Something neglected in all these discussions is the liturgical year itself and its contributions. "In the beginning God created heaven and earth," thus begins the Holy Scripture in the Book of Genesis. On the first day gave began creation, a gradual effort in which He fashioned everything for six days and then, on the seventh day, left it as it was. In light of the Resurrection, which occurred the day after the day of the rest, the Christian sees the eighth day as the beginning of a new creation, which is, in effect, a renewal and a re-vivification of the old creation. As Christ rose from the dead with the same body, but glorified and transformed (Philippians 3:21), so the Christian will at the end of time at the Last Judgment. But this process is not so removed from our current time and current needs.

"In the beginning God created heaven and earth," thus begins the Holy Scripture in the Book of Genesis. On the first day gave began creation, a gradual effort in which He fashioned everything for six days and then, on the seventh day, left it as it was. In light of the Resurrection, which occurred the day after the day of the rest, the Christian sees the eighth day as the beginning of a new creation, which is, in effect, a renewal and a re-vivification of the old creation. As Christ rose from the dead with the same body, but glorified and transformed (Philippians 3:21), so the Christian will at the end of time at the Last Judgment. But this process is not so removed from our current time and current needs.