Tip of the biretta to Mr. Alan Robinson for directing me to the photo gallery for St. George's church in Sudbury (London). Many will know that in the early to mid-20th century the pastor of St. George was Fr. Clement L. Russell, a priest who, much like Quintin Montgomery-Wright decades later, imported the Sarum rituals and aesthetics into the existing Roman praxis.

The church of St. George was built in a truly gothic style, albeit it with the inclusion of many features popular in England at the time: devotion to St. Joseph and Ss. Thomas More & John Fisher. St. Geroge was also the first post-Reformation (Deformation would be more accurate) church in England with a shrine to Our Lady of Walsingham. Russell managed an enormous boys choir and army of altar servers. He used his services as a way of giving young men something to do and a diversion to keep out of trouble. He had first and second Vespers for all feasts Double of the II Class or higher, as well as Mattins and Lauds for the great feasts. Quite the Englishman, he usually kept two candlesticks on his altar, per Sarum, and quibbled over the matter with the vicar general of Westminster. Russell told the vicar general that St. George's would sport six candlesticks when the rest of the parishes in the archdiocese finally started using two on ferial days and four on vigils and ember days.

All the photographs below come from

this page and belong entirely to St. George's Catholic Church. The images are British Catholicism at its finest. Pure liturgical fetish eye candy! Yum yum yum!

The Baptistry

The shrine and altar of Our Lady of Walsingham. Note the

very English, very sumptuous frontal. Much of the statuary

was carved from single pieces of wood on St. George's grounds.

Some fool wreckovated the sanctuary, but fear not!—we have images below of

liturgies during the Clementine years. Judging by the altar arrangement, I would

hypothesize that St. George is now in the hands of a "hermeneutic of continuity" priest.

The original sanctuary. Note the curtains around the altar, something still seen in medieval

English churches. Above the altar is a Rood, seen in other images below. The Rood

was not a proper screen, but the effort was admirable given the times.

Solemn high Mass. The choir sits—gasp!—in the Choir. Judging by where the ministers

are situated and the sitting posture of the congregation, I would hazard a guess that this

is the Gradual and that the celebrant and subdeacon are reading the Gospel while the deacon

prepares to proclaim the Word. Note the two lead cantors singing ("ruling"?) from the

lecturn in medio choro.

A nuptial Mass, again with full choir and lead cantors. Again, probably

the Gradual.

The annual procession with relics on St. George's day. Cardinal Griffin, archbishop of

Westminster, visited on this occasion.

This picture is, for some reason, my favorite of the lot. The tall candles at the corners of

the steps leading to the altar are an English tradition. The Missal appears to be resting on

a cushion rather than a stand. Don Quoex did this, too.

A Requiem Mass

A Byzantine priest of some stripe offers the Divine Liturgy at St. George's.

From his facial features, seen in other pictures, and the cut of his vestments I would

guess that he is either Arab (Melkite) or Greek rather than Slavic. At first I was

surprised to see this picture, but then again Dr. Adrian Fortescue also imported native English

elements into the Roman rite during his life time and held the Byzantine tradition in high esteem,

almost joining the Melkite Church in Lebanon.

St. George's must have been quite spectacular until Fr. Russell's death in 1965 following an accident.

Here is an article on St. George's and Fr. Russell from the Anglo-Catholic

Historical Society:

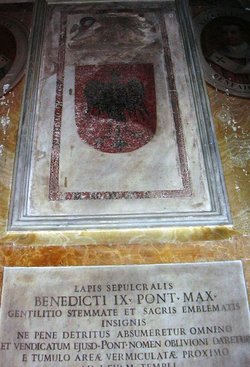

FEATURED ARTICLE

“THE ONLY ANGLICAN CHURCH IN COMMUNION WITH ROME”:

SAINT GEORGE’S SUDBURY AND FATHER CLEMENT LLOYD RUSSELL.

By John Martyn Harwood

I have loved, O Lord, the beauty of Thy House; and the place where Thy Glory dwelleth.

[Psalm 25, Douai version]

If any church’s tradition could be said to be sui generis, St George’s could and this was because of the vision of one man, its founder and priest for nearly forty years. Clement Lloyd Russell was born in 1884, the son of Henry Lloyd Russell, vicar of the Church of The Annunciation, Chislehurst and a prominent Tractarian. There is an early and amusing mention of him in the infamous report of the Royal Commission on Ecclesiastical Discipline (1906) which was established to put an end to “illegal” ritual practices in the Church of England. Among the hundreds of pages of evidence is an entry about The Annunciation, Chislehurst, on 18th September 1904. The vicar strongly refutes any charge of lawlessness, taking a traditional Tractarian position and mentioning examples of past episcopal approval. He does however become a little defensive when replying to the report of a “visitor” that the festival of Corpus Christi was solemnly kept. The notice in the church porch announcing this, he maintains, was “placed there by my son, and I told him, after I became aware of it, of my disapproval”.

This indicates that Clement’s position was a good deal more advanced than the respectable High Church ritualism of his father. However, the son never experienced or embraced anything resembling “baroque” Anglo-Catholicism but remained an Edwardian High Churchman and medievalist to the end.

The younger Russell was ordained a priest of the Church of England in 1908 and for a short time was one of a tribe of curates at St Andrew’s, Willesden Green. In 1910 he experienced a crisis of conscience and was received into the Roman Catholic Church. After almost no formal training (he always maintained that he knew practically nothing about Roman Moral Theology or Canon Law) he was ordained deacon in 1914 and priest in 1915. He was sent as curate to work under a tyrannical parish priest at the Holy Rosary Church in Marylebone, London.

SUDBURY

This was a low point in Father Russell’s life but in the early 1920s he received an offer, which had the approval of Cardinal Bourne, from a very wealthy lady who wished to fund the building of a new church in one of London’s growing suburbs. He found himself in the happy position of being able to choose the site, architect, style of building, furnishings and dedication of the new church and parish. The foundation stone was laid in November 1925 and Father Russell moved into the newly built presbytery a few months later. He remained there, never taking a holiday, until his death in 1965.

Saint George’s church, in the non-descript district of Sudbury, near Harrow-on-the-Hill, Middlesex, was completed in 1927 and solemnly consecrated (a rare occurrence in those days) on the 18th April 1928. Its architect was the almost forgotten Leonard Williams, a modest church builder who died before this, his last work, was completed. Again unusually, it was entirely free from debt. At a time when “side altars” were usually wooden stands for holding statues and flowerpots, St George’s possessed four properly consecrated stone altars, designed on English medieval lines, dedicated to St George (the high altar), Our Ladye (Fr Russell’s invariable spelling), the Archangel Michael, and St Thomas of Canterbury.

THE CHURCH

He that hewed timber afore out of the thick trees: was known to bring it to an excellent work.[Psalm 74, Prayer Book version]

The church from the outside still looks much as it did in 1927 and can be seen on its current website. It is a dignified perpendicular gothic building of warm stock brick and much stone dressing. The clergy house is joined to the church which can be accessed from it. The whole composition is very charming and romantic despite the clearing of many trees which used to surround it. There are two large bells, also properly consecrated and anointed.

But it was chiefly for its furnishings that St George’s was famous. Over many years Fr Russell acquired or had made innumerable objects of piety to adorn his new creation. Slowly the altars were all vested with rich frontals in all the liturgical colours – this meant at least six or seven sets for each of the four altars. Each also had the inevitable riddle posts with angels holding candles. Between these, curtains of the highest quality hung, again in the different colours. Canopied images of the dedicated saints stood above. All the woodwork was carved and nothing of plaster was allowed in the church even temporarily.

The rector, as Fr Russell was often called, had no objection to popular devotions and was not of the austere “Benedictine” school; however the devotions had to have medieval precedents. No images of the Sacred Heart or Our Lady of Lourdes were permitted but near the back of the church, opposite the main door, was a large oak “tableau” depicting the Five Wounds of Christ and with a carved statue of the Lord at its centre. This was of course a very popular cult in late medieval England. Above were emblazoned the words (and I quote from memory for the entire shrine has since disappeared): JHESU BY THYE WOUNDES FYVE: SHEWE ME THE WAYE TO VERTUYOUS LYFE.

For many years it remained a puzzle to new parishioners especially those of simple faith but eventually the shrine acquired its devotees.

Above the Lady altar, was enthroned, in September 1928, a beautiful carved image of Our Lady of Walsingham. This was the first one based on the ancient seal to be erected in a Roman Catholic church. It was only six years after Fr Hope Patten had placed his Walsingham statue in the parish church there. Of course Fr Russell knew of all that had been achieved by the Anglicans at Walsingham and was anxious to spread the devotion in his own Communion. Thereafter the appropriate Marian Antiphon was always sung after all evening services in front of her image. In 1933 a second statue of the Blessed Virgin was unveiled in the Lady Chapel: this was a magnificent alabaster carving of medieval origin, showing her standing and holding her Son and, in the other hand, a sceptre. It had been found in Devon, restored and presented to Fr Russell. Several experts claimed that it had originally formed part of the reredos behind the high altar of Exeter cathedral, and it still retained traces of colouring. A beautiful carved wooden screen enclosed the Lady chapel, decorated with images of Saints Lawrence and Katherine in memory of the last two chapels on the ancient pilgrims’ “Walsingham Way.”

This is only a partial description of the church’s contents; there were also two carved eagle lecterns, one of which stood in the centre of the choir for use by the cantors, and additions were still being made right up to the rector’s death. In 1962, for example, the huge rood beam, rood, statues of Saints Mary and John and attendant cherubim on “wheels” were re-gilded and in the same year expensive iron gates and a fine image of St John the Baptist were added to the Baptistery.

THE SERVICES

Those who still remember St George’s before 1965 will recall its liturgical life even more than the beauty of its furnishings. Starting from modest beginnings, Fr Russell gathered around him a team of enthusiastic helpers to form choir and servers to assist him in the offering of the rich round of services he desired. By the early 1950s he had established Sung Masses and Solemn Vespers on all Sundays and great festivals, with vespers being sung even on “Days of Devotion”, including all the feasts of the Apostles. Christmas was particularly well served with solemn first vespers; solemn matins and midnight mass; sung masses of the dawn and day (celebrated at9.30 and 10.30am respectively); solemn second vespers, procession and benediction and solemn vespers with procession on each of the following four days (they were all Days of Devotion!) The grandest and most fashionable Anglo-Catholic church in Edwardian days could not have done more.

The number of singers and servers, who were all housed in the sanctuary, rarely exceeded thirty-five which the rector considered a rather inadequate figure though most clerical visitors viewed it with envy. Needless to say those who served at the high altar were not only rigorously trained but were richly attired. The cantors wore copes, the rest of the choir and most servers, full gathered surplices, like those shown on portraits of Tudor bishops, with enormous sleeves and in length reaching below the knee. Famous (or notorious) were the apparelled albs and amices worn by the acolytes and thurifer (even the apparels came in complete sets of liturgical colours) and the alb and tunicle of the crucifer. Fresh chasubles and copes for the celebrant were often added when Fr Russell heard of Anglo-Catholic churches which had abandoned “gothic” styles. He had some kind of source of secret information about such matters. Everything used in the worship of God was of the highest quality down to the candles, incense, altar breads and wine. The music of course was strictly plainsong and under the direction of men who had Benedictine monastic training.

The number of sung services was actually increasing in the years just before Fr Russell’s death whereas elsewhere, both in the Roman Catholic Church and in the Church of England, they were in steep decline. I can remember when matins on Pentecost Eve was introduced for the first time, in 1959. However, it cannot be said that any services at St George’s other than low masses were ever very well attended. This worried Fr Russell not at all. When the church was first opened only twenty Roman Catholics lived in the area and there was no real need for a new parish at all. In 1962 mass attendance was found to be 1,175 souls. The rector arranged worship in the same way for both numbers. On one dark evening, a server nervously told him, before vespers began, that there was no one in the church at all. “Nonsense” he replied, “the nave is full of angels”.

THE MAN

As can be guessed, Fr Russell was not free of eccentricities. Life in his clergy house was a strain for most curates, who did not tend to stay long. First there was the Dickensian clutter of vestment presses, cuckoo clocks (all set at slightly different times, though never British summer time), large cats as eccentric as their master, books and antique silver. Then there was the conceit that he was a beleaguered Anglo-Catholic vicar liable to be disciplined by his diocesan, though successive Cardinals actually showed astonishing indulgence towards him (it should be remembered that before the Second Vatican Council the overriding priority of the Roman Catholic hierarchy in England was the establishment of a RC school in every parish; Fr Russell never attempted to do this and never even mentioned the need for one.) “The Archbishop is coming” he would say, “We must hide the acolytes’ albs” or: “When I am dead they will come and turn all my vestments into bed covers just as the Reformers did”. Actually, in a sense, this prophecy was fulfilled. Some wag had once called St George’s “The only Anglican church in communion with Rome”. This was probably intended as a taunt but Fr Russell wore the label with great pride (perhaps he remembered his father’s church at the start of the Twentieth Century) and would often quote it to startled new-comers.

Fr Russell wrote everything by hand using the most extraordinary late medieval Gothic script. Many parishioners claimed they could not read the notices in the church porch at all. The local postman was made of sterner stuff and took great pride in being able to deliver all the rector’s letters without difficulty. He especially approved of the priest’s complete non-use of abbreviations – Saint not St or London North West rather than NW. How Father would have hated (it still makes me feel slightly guilty) my use of “Fr” in this article.

Often such highly motivated men can be ill-mannered or off-hand; Fr Russell by contrast was the mildest and most easy-going of souls, other-worldly and quite without authoritarianism. Servers and young choir members would sometimes ask him to inscribe their missals. He always used the same text for this, taken from the Book of Ecclesiastes in the Authorized Version: “Remember now thy Creator in the days of thy youth, while the evil days come not, nor the years draw nigh, when thou shalt say, I have no pleasure in them”. In his later years he allowed a poor Irishman who drank rather too much to live permanently in the clergy house and provided for him generously in his will.

Much was rumoured about Fr Russell’s supposed fascist leanings. I believe them greatly exaggerated. He certainly supported Mussolini in the 1930s but so did many others, and he admired General Franco all his life. Hitler he wrote openly against in the parish magazine after the war started. I believe that the fascist rumours were partly based on the certain fact that two members of his choir were prominent members of Mosley’s Party and later were conscientious objectors. In truth Father was not much interested in events that took place after 1530.

THE AFTERMATH

But now they break down all the carved work thereof: with axes and hammers.

[Psalm 74, Prayer Book version]

Clement Lloyd Russell was hit by a car, crossing the road outside his church, and died soon afterwards, on 11th January 1965. He was 80 but in good health and still running St George’s along usual lines. His death at least saved him from having to make inevitable and difficult choices, for the Second Vatican Council was in full swing. Already low masses at St George’s were being said in English. Fr Russell’s tradition would have received little sympathy from the new sort of Roman Catholic who regarded the Council documents as on par with the Four Gospels, nor from their conservative opponents, Anglo-Irish and stubbornly philistine, nor even from modern Anglo-Catholics eagerly following every trend of the Liturgical Movement. In the mid Sixties his ideals of liturgical worship could not have been more unfashionable. This needs to be clearly stated. It should also be added that he had almost no sympathy with the budding ecumenical movement. Without of course realising it, he was in his spirituality and his priorities, extremely close to Eastern Orthodoxy. If any reader thinks this far-fetched, read Russell’s own summary of his aims, which concludes this article.

The priest appointed as his successor, Wilfrid Purney, tried to maintain some continuity but the looming liturgical changes from above demoralised Fr Russell’s old supporters. The men’s choir was disbanded in June 1966 and most of the servers ceased to attend about the same time. Services began to resemble those elsewhere in the archdiocese. Fr Purney however, always kept the church looking as it had always done and no “re-ordering” was permitted. After his death the long-delayed deluge came with the arrival of those “who knew not Joseph”. Because of the late date of the building and its furnishings, those opposed to major change could not appeal to the law or preservation societies. Between 1990 and 1996 St George’s interior was completely gutted. Most of the furnishings and hangings disappeared, the consecrated stone altars were desecrated and destroyed and an extraordinary octagonal-shaped altar was placed in the centre of the church. But it would be fruitless, and perhaps libellous, to continue. Fr Russell would perhaps have simply remarked that King Edward VI’s visitors had returned to earth.

CONCLUSION

I want to conclude by quoting from Fr Russell’s own words because it is important to understand that he was much more than just a “character”. Here he is writing in the parish magazine in the 1940s, but he very often expressed himself in similar terms, as I heard him do so several times:

And beyond all, I want the sanctuary, especially at sung mass and at vespers and benediction, to speak to people of the glories of Heaven, and that, as far as is humanly possible, there shall be gathered there a splendour of colour and light, beauty of vesture, and ordered movement that compels the most wandering and distracted of undisciplined minds to realise that something far, far more than the satisfaction of human devotion is being accomplished – that the eternal and invisible GOD is being worshipped, and that all that is being done, is performed to render the easier, a response to the invitation “Sursum Corda!” There, at all events, is and has been my great endeavour.