|

| "Mr. President, may I be?" |

Last week I passingly

mentioned an author who deserves more thought than a brief allusion in a post about liturgy. Robert Nisbet wrote a doctorate at Berkeley in 1939 and, with a few other authors, eventually published a book that contributed to a coherent conservative political thought in the 20th century. Like the "Wizard of Piety Hill" and unlike William Buckley he was more interested in social problems and social institutions than in Washingtonian affairs. His specialty as a sociologist was the history of these societal institutions. To winnow his thought into the generic "government bad, free market good" strain undersells his tremendous insights. If anything he understood the post-industrial society which followed the War to be just as vacuous as the New Deal welfare state it replaced. His

Quest for Community focuses on the role of government as the great social leveler (like a bulldozer), but the commentary applies to all forms of centralization. Contrary to the ravings of modern libertarians, he understood that individualism was the consequence of centralization because it eliminated "intermediary" layers of society where people traditionally derived their identities.

I cannot say with certainty whether or not he was a Catholic, but his writing betrays a strong sympathy for the place of the Church in pre-Reformation Europe and he penned articles for

Crisis in the 1980s. Much of his commentary from

Quest for Community readily applies to contemporary isolation created by social media, but also to the loss of identity among Catholics in the Church, not merely individuals, but priests, too; the loss of minor orders, local chivalric chapters (not the Knights of Malta), respect for the primacy of tradition as an authority can all be read into Nisbet. Rather than interpret his writings I have reproduced the most illuminating passages below for conversation in the comment box.

* * *

"....powerful processes of rationalization and bureaucratization....have led, Weber declared, to a supremacy in modern times of the impersonal office and of mechanical systems of administration within which the primary unities of social life have become indistinct and tenuous."

"....there is agreement upon certain social characteristics of the Middle Ages, irrespective of the moral inferences to be drawn from them. The first is the pre-eminence in medieval society—in its economy, religion, and morality—of the small social group. From such organization as family, gild,village community, and monastery flowed most of the cultural life of the age.... The reality of the separate, autonomous individual was as indistinct as that of centralized political power. Both were subordinated to the immense range of association that lay intermediate to individual and ruler and that included such groups as the patriarchal family, the gild, the church, feudal class, and the village community."

"In the Middles Ages, allowing for all obliquities and transgressions, the ethic of religion and the ethic of community were one. It was indeed this oneness, so often repressive of individual faith, so often corrupting to the purity of individual devotion, that the religious reformers like Wyclif, Hus, Calvin, and others were to seek strenuously to dissolve."

"Two points only are in need of stress here. The first is the derivation of group solidarity from the core of the indispensable functions each group performed in the lives of its members.... The second point to stress is that the solidarity of each functional group was possible only in an environment of authority where central power was weak and fluctuating.... It is indeed this curtailment of group rights by the rising power of the central political government that forms one of the most revolutionary movements of modern history."

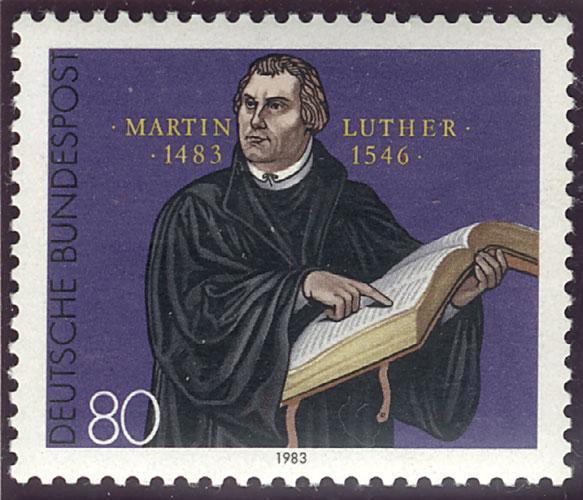

"At the back of this decline of religious communalism are certain decisive conflicts of authority and allegiance. These are conflicts, if we like, between the individual and Rome, dramatized by Luther's nailing of the theses to the church door. But, more fundamentally, they are conflicts between Church and sect, between Church and family, between State and Church, and between businessman and canon law. The Reformation becomes a vast arena of conflict of authority among institutions for the loyalty of individuals in such matters as marriage, education, control of economic activity, welfare, and salvation. Basically, we are dealing with two momentous conceptions of religion: on the one hand, a conception that vests in the Church alone control of man's spiritual, moral and economic existence; on the other, a conception that insists upon restricting the sphere of religion to matters of individual faith and transferring to other institutions, notably the State, responsibilities of a secular sort."

"In Protestantism there has been a persistent belief that to externalize religion is to degrade it. Only in the privacy of the individual soul can religion remain pure. There has been little sympathy for the communal, sacramental, and disciplinary aspects of religion. Protestant condemnation of the monasteries and ecclesiastical courts sprang from a temper of mind that could also look with favor on the separation of marriage from the Church, that could prohibit ecclesiastical celibacy, reduce the number of feast days, and ban relics, scapularies, images, and holy pictures."

"Three principle elements of Christianity were left in Protestant theology: the lone individual, an omnipotent, distant God, and divine grace."

"At times, to be sure, as in the Geneva of Calvin, the organizational side of the new religion could be almost as stiff as, and perhaps more tyrannical than, anything in the Roman Church. There is indeed a frequent tendency among historians to overlook the sociological side of early Protestantism.... almost from the beginning, the spread of Protestantism is to be seen in terms of revolt against, and the emancipation from, those strongly hierarchical and sacramental aspects of religion which reinforced the idea of religion as community."

"As Protestantism sought to reassimilate men in the invisible community of God, capitalism sought to reassimilate them in the impersonal and rational framework of the free market. As in Protestantism, the individual, rather than the group, becomes the central unit. But instead of pure faith, individual profit becomes the mainspring of activity."

"In the beginning, in France, England, and elsewhere, the State is no more than a limited tie between military lord and his men. The earliest distinct function of the king is that of leadership in war. But to the military function is added, in time, other functions of a legal, juridical, economic, and even religious nature, and, over a long period, we can see the passage of the State from an exclusively military association to one incorporating almost every aspect of life."

"The modern State is monistic; its authority extends directly to all individuals within its boundaries. So-called diplomatic immunities are but the last manifestation of a larger complex of immunities which once involved a large number of internal religion, economic, and kinship authorities."

"The political rulers may have been less interested in the theological elements of either Catholicism or Protestantism than they were in breaking the secular power of the Catholic Church, but the consequence was nevertheless a favorable one to such men as Luther."

"To Rousseau the real oppressions in life were those of traditional society—class, church, school, and patriarchal family. How much greater the realm of individual freedom if the constraints of these bodies could but be transmuted into the single, impersonal structure of the General Will arising out of the consciousness of all persons in the State."

"Contemporary prophets of the totalitarian community seek, with all the techniques of modern science at their disposal, to transmute popular cravings for community into a millennial sense of participation in heavenly power on earth. When suffused by popular spiritual devotions, the political part becomes more than a party. It becomes a moral community of almost religious intensity, a deeply evocative symbol of collective, redemptive purpose...."

"The Roman emphasis on legal centralization, upon the superiority of the ruler to all other forms of authority, including custom, and the general political perspective of Roman law could not but have had strong appeal to one of the Politiques."

"It follows that no association within the commonwealth can be allowed to enjoy an independent existence in the sphere of public law."

"Faith in God and incentives toward religious piety were held by the early Protestants to lie in the self-sufficing individual, even as incentives toward work were declared by the economic rationalist to be similarly embedded in the very nature of the individual. Hence, the Protestant leaders gave little direct attention to the social reinforements of conscience and faith."