In a previous post we looked at the first millennium Roman liturgy from a textual and historical perspective, at how the traditional liturgy as we have it today evolved from a remarkably similar Mass around the year 800 AD. Today I just want to "throw" some material at you for your own edification once again, this time pertaining to the setting of the first millennium and medieval Roman liturgy, namely the original St. Peter's basilica. Most of what I have below is republished from last year, but with many improvements.

The original St. Peter's basilica was begun by Emperor Constantine over a shrine on Vatican Hill here Christians had venerated what tradition tells us was the place of St. Peter's burial since the first century—St. Peter's bones were not actually discovered until the reign of Pius XII. The basilica was completed in 360, but constantly remodeled. Originally the tomb of the first Pope of Rome was in the apse of the basilica, behind the altar. Tidal flow of pilgrims necessitated switching these two. A more elaborate throne for the Pope was constructed, as consecration of the Bishop of Rome became more usual at St. Peter's. The proliferation of Papal burials at St. Peter's and a series of ninth century invasions by Saracens necessitated further renovations. One such remodel, around the time of Leo IV, led to an altar embroidered in precious stones, ambos and doors of silver, and mosaics taken from the finest Eastern churches. Like most Roman basilicas, there was a group of canons attached to the church.

|

| from: bible-architecture.info |

A cloister preceded the entrance. I cannot help but think of Dr. Laurence Hemming's theory of the Catholic churches as temples, as fulfillment of the Temple of Jerusalem. The cloister here is more of an enclosed sacred courtyard than anything monastic. It functioned as a gathering place for people to prepare for Mass, an eschaton—a place between the world and eternity. A pineapple, which I believe predates the Christian era, sat at the center of the cloister. The faithful, as late as the eighth century, washed their hands for Communion at the fountains in this area—although reception on the hand differed drastically from the modern practice. In all, it is like the courtyards of the Temples of Solomon and Herod: a gateway through which the faithful would leave the world and prepare for the Divine. Sort of the story of salvation, eh?

|

| Drawing of how the mosaics on the façade of the basilica, as restored by Innocent III, would have been arranged. source: chestofbooks.com |

The inside was very much that of a Roman basilica which, before the Christian age, just meant an indoor public gathering place for Romans. The nave would be lined with colonnade, but statuary and imagery was sparse and likely introduced in the early second millennium. The primary source of color would have been through patterns and mosaics on the ceiling, particularly in the apse. While Byzantine churches tend to either depict Christ as a child in our Lady's arms or Christ the Pantocrator in the apse, Roman churches vary more, and St. Peter's would have been no exception. St. Mary Major's apse bears Christ and our Lady seats in power, while the Lateran depicts Him ascended above all the saints—and above us, lest we forget, and St. Paul outside the Wall depicts Him in blessing but with a book of judgment. St. Peter's might have also had some variation of Christ in the apse, above the stationary Papal throne.

The altar was both ad orientem and versus populum, a rarity outside of Rome. During the Canon the faithful would go into the transepts and the aisles of the nave and face eastward with the priest, meaning they did not "see" the change on the altar. Curtains may have been drawn regardless, guaranteeing people did not see the consecration until the Middle Ages at least.

The populistic arrangement, of the Pope facing the people, gives us a clear indication of where the reformers discovered their "Mass as assembly" idea, but neglects the very hierarchical arrangement, which the Bishop of Rome elevated, surrounded by his counsel and the servants of the faithful in Holy Orders. Certainly a more popularly accessible structure than a Tridentine pontifical Mass from the throne, but not remotely as democratic as the reformers would have us believe. Papal Mass continued their arrangement through 1964, the year of the last Papal Mass.

The altar was both ad orientem and versus populum, a rarity outside of Rome. During the Canon the faithful would go into the transepts and the aisles of the nave and face eastward with the priest, meaning they did not "see" the change on the altar. Curtains may have been drawn regardless, guaranteeing people did not see the consecration until the Middle Ages at least.

The populistic arrangement, of the Pope facing the people, gives us a clear indication of where the reformers discovered their "Mass as assembly" idea, but neglects the very hierarchical arrangement, which the Bishop of Rome elevated, surrounded by his counsel and the servants of the faithful in Holy Orders. Certainly a more popularly accessible structure than a Tridentine pontifical Mass from the throne, but not remotely as democratic as the reformers would have us believe. Papal Mass continued their arrangement through 1964, the year of the last Papal Mass.

|

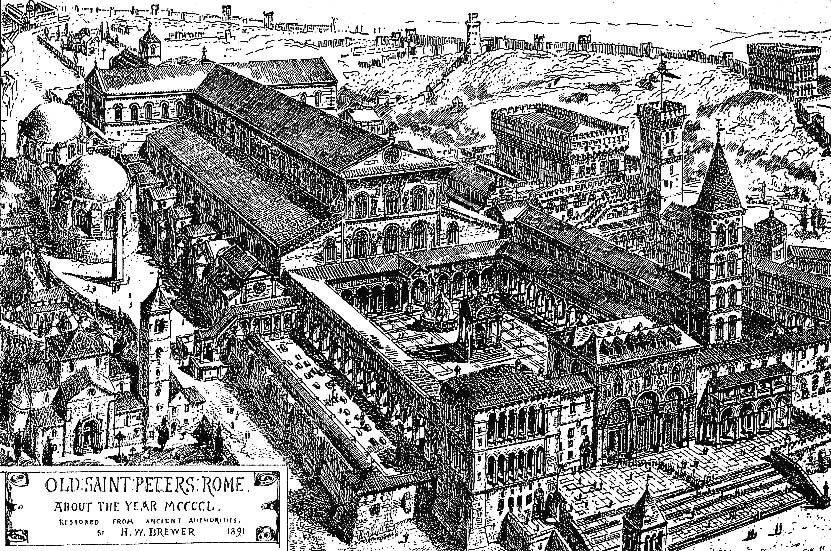

| St. Peter's basilica around the year 1450 (taken from wikipedia) |

|

| A cross-section of the old basilica (from saintpetersbasilica.org) |

Neglect during the Avignon papacy left the Roman basilicas in ruins, St. Peter's included. The roof of the basilica and its re-enforcement were both wood, which had long rotted. Instability eventually caused the walls and foundations to crack and, although many maintained the basilica was still usable, the decision was made to replace it in 1505 by Pope Julius II. The decision rightly sent Romans into uproar, as the old church had been used by the City and by saints for twelve centuries.

|

| Inside the old St. Peter's notice the elevated altar surrounded by the twisting arches. St. Peter's tomb was below. Above is the fatal ceiling. (image taken from jamesbrantley.net) |

The fate of much of the original basilica is unknown. Elements of the portico survived, as did the Papal tombs. St. Peter's tomb received its own chapel, named for the Pope who built it. The high altar was retained and en-capsuled in the new altar. The altar sanctuary had been walled from the nave by winding pillars, supposedly taken from the Temple of Solomon. They were destroyed, although their design is retained in the new basilica's baldacchino.

|

| Another long view inside the old basilica |

Below is a reconstruction of how the sanctuary would have looked during the Middle Ages. Note the wall and doors, much like an iconostasis, betwixt the sanctuary and nave. The semi-circular benches around the Papal throne were for the canons of the basilica, the seven deacons of Rome, the archpriest, and the cardinals. The doors on the sides might have been either for the deacons, for those administering Holy Communion to the people in the transepts, or for those visiting the tomb below the sanctuary.

|

| From New Liturgical Movement |

The reconstruction below, however, seems to aim at imitating a medieval version of St. Peter's basilica. The above image, of the basilica in the first millennium, shows a church which has not yet undergone various renovations consequent to medieval piety and style: the barrier above is more of a railing than a wall, there are side-chapels below but not above, and curtains around the altar—emphasizing the mystery of it all, and colonnade around the Papal throne—pointing to the unique place in the sanctuary of the chair of Peter. The walls are also sparser in the pre-Middle Ages image above. I suspect the person who created these images is of the Byzantine tradition, as he has put icons above the altars as decoration rather than more Romanesque mosaics and paintings. Still, quite an effort.

Below is a video from the same source showing a detailed view of the old basilica. I always found the old pineapple funny. It is a pagan bronze work dating to the first century and which resided in the Vatican square for no reason other than its pre-dating the basilica.

"During the Canon the faithful would go into the transepts and the aisles of the nave and face eastward with the priest, meaning they did not "see" the change on the altar."

ReplyDeleteI've heard this contested.

Where can one find sources defending this?

The idea that the faithful looked eastward at any specific point in the mass is conjectural, as is so much about the liturgy before the 8th century. However, the general mandate that Christian people look eastward to pray is anciently attested.

ReplyDeleteIt is noteworthy in this discussion that ancient basilican churches from the Roman period face every possible direction, often because they were remodeled from or built over existing, non-ecclesiastical structures. This includes many of the titular churches of Rome. (Santa Sabina, for example, was built north to south.) Mass facing the people has always been customary in these churches. In most, that means facing east--but that is not always the case.

This practice of facing the people is distinctly of Rome, and I know of no ancient evidence for it anywhere else. The ancient--and I mean ancient--churches of Asia Minor and the Levant ALL are built on an east west axis, and all the ancient liturgies specify or imply that all prayers and the consecration be said facing east--i.e. toward the icons on the wall, not towards the people. This seems to have been the case even at Dura Europos, which is actually quite startling, if true.

The distinctiveness of the Roman practice puzzles me. It seems so disconnected from what was going on elsewhere.