|

Such is the contemporary state of the Roman liturgy. Many readers have asked over the last two years what the point of the liturgy is. They are being cynical. The question carries the utmost gravity. Is it a divinely imparted ritual with its own powers? Is it a set of didactic actions that ornament the more important mechanical acts of transmitting grace? What is it? If we do not know what the liturgy is, then we are truly lost. The liturgy, in my own private opinion, is the sensus fidelium of the Church expressed according to separate, non-contradicting traditions and lived out in the Church universal. There is no citation for this definition in an ecumenical council—nor is there a definition of the Resurrection. Previous generations needed no definitions or binding statements to understand the relationship between the liturgy and the faith. If they believed it, they prayed it. They did not leave what they believed out of their worship, nor did they believe in novelties unfounded in the traditions of the Church. Liturgy does not merely teach belief and transmit grace. It revives and renews the sacred mysteries of Christ in time for the faithful. In doing so, one encounters Christ, the angels and saints, and glimpses into the greater spiritual reality of the Lord while remaining on earth, blurring the lines which separate the eternal and the temporal. One leaves the liturgy and the "mystical supper" of Christ not only having learned what to believe, but also how to believe when he returns to the world outside the temple.

Christ taught simply. His teachings tell the listener as much about how to engage Him as much as they do what to think of Him. Chesterton wrote that when he first read the Gospel, contrary to everything he was told about a kind rabbi divinized by his followers, Jesus spoke authoritatively as God. As God, He commanded love, fidelity, and trust in Him as well as care and attention towards one's neighbor. Above all, He taught the forgiveness of sins and the metanoia of the sinner. The last part concerns us. How does one orient one's self to God and away from sin? How does one see the world and God as He wishes? In conjunction with being the setting for the Sacraments, where the Holy Spirit acts and makes the work of Christ immediately accessible to the believer, the liturgy shows us this. It only makes sense. When a friend asks about the Catholic faith, one does not give him a catechism. One takes him to Mass or the Divine Liturgy.

"I have passed on to you what I have received," St. Paul wrote to the Church in Corinth some time in the 50s, merely a generation after the Passion of the Lord. The Apostle to the Gentiles passed on to the Corinthians both the tradition of the Lord's work and the tradition of what He commanded His followers to do. The two were inseparable. Belief and the primitive liturgy were received by believers simultaneously. They did not remain static, however. Passing on something does not preclude its development, its clearer enunciation, its deepening. Chapter 23 of St. Vincent of Lerins' Commonitorium applies to the liturgy as much as to doctrine:

Local churches developed their liturgical rites around their own settings, needs, and cultural tendencies. The Roman rite is, to say the least, highly efficient. More so than the Eastern rites, replete with hymns and elaborate gestures, the Roman rite uses the words of Holy Writ as its almost exclusive textual basis for the propers and many of the prayers, reflective of the Roman legal tradition's emphasis on the binding power of authoritative words. The more philosophical Greeks had a mystical and excessive liturgy consonant with its philosophical tradition. And the various far Eastern rites too reveal their origins. The Roman Patriarchate tolerated variation more than any other patriarchate until Trent, permitting, often begrudgingly, "dialects" of the Roman rite like the French, English, and Portuguese uses as well as further departures like Toledo, Milan, and L'Aquila. The multiplicity of uses in the Latin Church multiplied the spiritual wealth of the Western Church and gave her saints and thinkers recognized across national borders. Uses were often suppressed, but local variety was accepted as the norm with Rome as the original, the standard, the canon. One can trim the branches of a tree, but not the trunk.

These various dialects teach the Christian to perceive the world in a divine language. Language, Noam Chomsky begrudgingly admits, is something for which human beings seem uniquely wired. Language creates learning, interaction, and introspection. The liturgy, in a very real way, makes all these things possible with the Holy Trinity. The liturgy of the Church, Alexander Schmemann taught, is the continued presence of the Lord in the world and in time. Laurence Hemming develops this idea and notes the medieval concept of the liturgy as the opus Dei, the work of God which man engages and shares. In prior times, the bells of monasteries and cathedrals signaled the various canonical hours and stages of the Mass in town. The liturgy was the pulse of the community, not a feature of it. Schmemann's interpretation of the entirety of the liturgy of the Church as Christ's continued presence is not verified by baroque and modern writers, but by the liturgy itself. In it, the Christian meets God as He is, not as He is imagined to be or desired. The understanding of God in the liturgy may be deepened or hallowed by previous generations, but the sensus cannot be changed. The literal encounter with God liturgically, but not exclusively in the Sacraments, finds confirmation in the oldest texts of the Church. On Holy Saturday the deacon, in the blessing of the Paschal candle, sings of "this night," not "a night we remember," as the night of the passage to salvation. Then the cynosures of pre-Incarnational salvation history are recounted by the lectors, the story of the fall of both Man and creation. Then, water, a symbol of creation and the fundamental element of creation itself, is blessed and made into the matter of our salvation in Christ, Who Himself first made it holy in creating it and then re-sanctified it by seeking St. John's baptism in the Jordan. He brought the world back into Himself in that act and segmented a new creation that the baptized join. So water is blessed and sprinkled on the faithful. Catechumens join that new creation in Baptism themselves. This transcends decoration around simple Sacraments of Baptism and Communion. Indeed, it is this liturgical context that those Sacraments make sense. The re-visitation of the divine mysteries continues in the morning with the Mass, "I am risen and am still with you." The Church uses the psalm in the present tense and does not adapt it to a commemorative tone. Similarly, the collect of Pascha refers to the Resurrection as having transpired hodierna. The Byzantine rite also speaks of the Resurrection as a current reality, singing countless times "Christ is risen from the dead...." On Holy Saturday, Pascha, and the other Sundays, ferial days, and feasts of the year, the faithful see the Trinity, the Sacraments, and the Saints as they really are and are united to heaven in the sacred rites, when God comes down from heaven and gives the Christian a glimpse above in a heavenly tongue.

To those who think this "high" interpretation inappropriate or misguided, the author poses the question: why consecrate a church? The objection to interpreting the liturgy as a very real thing which imbues the sensus fidelium by bringing the faithful to the sacred acts of Christ usually rests on the misguided belief that a religious act is either real or symbolic, but never both. Yet Baptism is both real and symbolic. It symbolizes creation, restoration, the eighth day, the Divine Adoption, and the cleansing of spiritual dirt. And still, it actually accomplishes all these things and incorporates a person into the Body of Christ, the Church. The Cathedral of Our Savior at the Lateran palace in Rome was the first church ever to be consecrated in the sense that churches are consecrated. It is not a Sacrament and the rejection of a high view of the liturgy would necessarily elicit one to interpret the actions as a series of exorcisms and drawn-out, pious actions of instruction. Does the church then become a house of God? Can there be such a thing as a house of God in a post-Mosaic Law Church without the authority of the Church to develop and deepen its tradition to allow for such an act of consecration? The Church does indeed symbolize the Temple of Jerusalem and the future New Jerusalem of heaven, but it is actually a very real house of God where, as in heaven, God lives and dwells and, for a few hours a week, acts. If the liturgy is anything less, then it is just bad literature.

The purpose of the liturgy, especially during the great periods of the year, is to unite the faithful to God so that they might know Him and save their souls. He gathers them to Himself and to His new Jerusalem, the Church, and to His Body, again, the Church. The belief and the sensus fidelium of the Church is diffused among the various rites and usages the Church enjoins and has practiced through out the ages. Christ's Body, the Church on earth, is much like His physical body when He was present among us in flesh in that it is organic and prone to growth. I recall years ago reading interviews with both a prominent sedevacantist and a priest of the FSSPX. Both were asked if a pope could create a new rite of Mass and both answered "In theory, yes, but the New Mas is bad, so we reject it." I think a more prudent reply excludes the possibility that the pope, or any bishop, can create a new liturgy or discard large portions of the old liturgy. Many of the additions to the Roman rite over the years—introductory rites in the Office, hymns, prayers before the altar, the offertory, the monastic choir ceremonies, the Eastern feasts imported etc—were just that, additions, neither replacements nor fabrications. If we concede this point, then we lose part of the sensus fidelium and instead embrace the inner-mind of some dodgy bishop. Worse yet, we lose the greater meaning of the mysteries and lessen the Sacraments, turning them into transmission channels for grace and nothing more. To retain the sensus fidelium and keep the faith, we ought to guard the liturgy of the Church with Davidic fortitude lest we embrace Christ as we want Him to be and not as He actually is.

My fellow Americans: Happy Thanksgiving. Fast tomorrow!

"But some one will say, perhaps, Shall there, then, be no progress in Christ's Church? Certainly; all possible progress. For what being is there, so envious of men, so full of hatred to God, who would seek to forbid it? Yet on condition that it be real progress, not alteration of the faith. For progress requires that the subject be enlarged in itself, alteration, that it be transformed into something else. The intelligence, then, the knowledge, the wisdom, as well of individuals as of all, as well of one man as of the whole Church, ought, in the course of ages and centuries, to increase and make much and vigorous progress; but yet only in its own kind; that is to say, in the same doctrine, in the same sense, and in the same meaning."

Local churches developed their liturgical rites around their own settings, needs, and cultural tendencies. The Roman rite is, to say the least, highly efficient. More so than the Eastern rites, replete with hymns and elaborate gestures, the Roman rite uses the words of Holy Writ as its almost exclusive textual basis for the propers and many of the prayers, reflective of the Roman legal tradition's emphasis on the binding power of authoritative words. The more philosophical Greeks had a mystical and excessive liturgy consonant with its philosophical tradition. And the various far Eastern rites too reveal their origins. The Roman Patriarchate tolerated variation more than any other patriarchate until Trent, permitting, often begrudgingly, "dialects" of the Roman rite like the French, English, and Portuguese uses as well as further departures like Toledo, Milan, and L'Aquila. The multiplicity of uses in the Latin Church multiplied the spiritual wealth of the Western Church and gave her saints and thinkers recognized across national borders. Uses were often suppressed, but local variety was accepted as the norm with Rome as the original, the standard, the canon. One can trim the branches of a tree, but not the trunk.

|

| "That we may receive the King of All, invisibly escorted by angelic hosts." source: preachersinstitute.com |

|

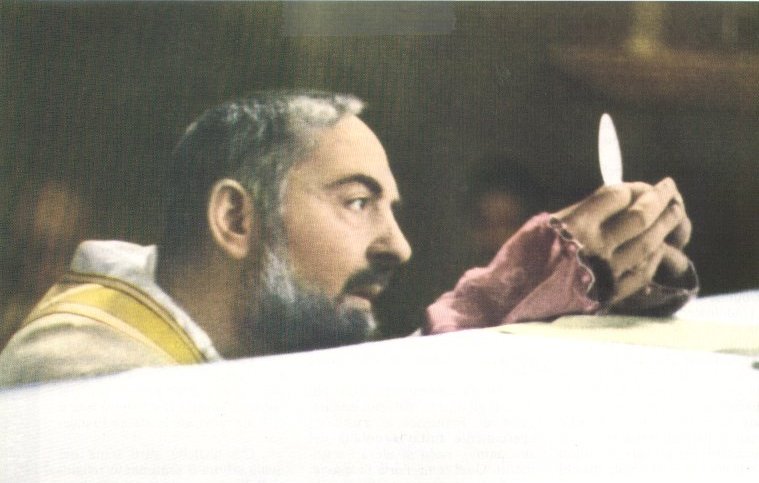

| "All of Paradise is close to the altar when I celebrate Mass. The angels attend my Mass in legions. The Virgin assists me." |

The purpose of the liturgy, especially during the great periods of the year, is to unite the faithful to God so that they might know Him and save their souls. He gathers them to Himself and to His new Jerusalem, the Church, and to His Body, again, the Church. The belief and the sensus fidelium of the Church is diffused among the various rites and usages the Church enjoins and has practiced through out the ages. Christ's Body, the Church on earth, is much like His physical body when He was present among us in flesh in that it is organic and prone to growth. I recall years ago reading interviews with both a prominent sedevacantist and a priest of the FSSPX. Both were asked if a pope could create a new rite of Mass and both answered "In theory, yes, but the New Mas is bad, so we reject it." I think a more prudent reply excludes the possibility that the pope, or any bishop, can create a new liturgy or discard large portions of the old liturgy. Many of the additions to the Roman rite over the years—introductory rites in the Office, hymns, prayers before the altar, the offertory, the monastic choir ceremonies, the Eastern feasts imported etc—were just that, additions, neither replacements nor fabrications. If we concede this point, then we lose part of the sensus fidelium and instead embrace the inner-mind of some dodgy bishop. Worse yet, we lose the greater meaning of the mysteries and lessen the Sacraments, turning them into transmission channels for grace and nothing more. To retain the sensus fidelium and keep the faith, we ought to guard the liturgy of the Church with Davidic fortitude lest we embrace Christ as we want Him to be and not as He actually is.

My fellow Americans: Happy Thanksgiving. Fast tomorrow!

Liturgy is the waking memory of the Church. That is my own, Tolkienian, view of liturgy.

ReplyDeleteSomething just dawned upon me. You are very strongly opposed to the reversal of the orandi credendi formula but the fact is, that when the Nicene-Constantinopolian Creed was put into the liturgy it is the lex credendi which preceded the lex orandi.

ReplyDeleteAnd what you say: " The liturgy, in my own private opinion, is the sensus fidelium of the Church expressed according to separate, non-contradicting traditions and lived out in the Church universal. " supports the reversal.

DeleteI fail to see how the addition of the Creed—and I supported additions above—corresponds to the outright overhaul of entire rites and large portions of the liturgy by individual men and their committees, done to advance their own outlooks at the cost of a spiritual reality guided by the Holy Spirit and fleshed out by both saints and ordinary men. The Trinity and Divinity of Christ had long been celebrated in the liturgy, both in feasts and prayers. The Latin Church adapted the Creed liturgically rather late. If anything, it acknowledged something that was already a reality in the Church. The insertion of the Creed would be a problem if it was done on novel grounds or to introduce new things into worship and the faith (as the 0th century changes did)—to say so though would suggest the Church did not hold Christ divine or believe in the Trinity until Nicaea....

DeleteThe reversal of the maxim was all about control, as was the rest of Mediator Dei's novelties (art. 58). I will quote Aidan Kavanagh:

"To reverse [lex orandi lex credendi], subordinating the standard of worship to the standard of belief, makes a shambles of the dialectic of revelation. It was a Presence, not faith, which drew Moses to the burning bush, and what happened there was a revelation, not a seminar. It was a Presence, not faith, which drew the disciples to Jesus, and what happened was not an educational program but his revelation to them of himself as the long-promised Annointed One, the redeeming because reconciling Messiah-Christos. Their lives, like that of Moses, were changed radically by that encounter with a Presence which upended all their ordinary expectations. Their descendants in faith have been adjusting to that change ever since, drawn into assembly by that same Presence, finding there always the troublesome upset of change in their lives of faith to which they must adjust still. Here is where their lives are regularly being constituted and reconstituted under grace. Which is why lex supplicandi legem statuat credendi."

With lex Orandi, Mediator Dei, and Pius XII, I find the issue to be a simple one. If people throughout church history and in all the traditions have been saying one thing, then one lone pope comes along and says the opposite, I will presume it is the pope who is in error and NOT everyone else through the centuries.

Delete"The Pope speaks infallibly only when he speaks with the voice of the church and her unbroken traditions. The idea that his brain is an organ of the Holy Spirit is an innovation."- George Tyrrell

I was speaking from the angle where you considered the reversal of the phrase almost as a heresy. To me, the reversal of the phrase itself is very legitimate. I don't support the "overhaul", but the phrase itself sounds as legitimate. Because after heretical crises the Church emphasized certain points of doctrine by inserting certain phrases in the liturgy.

DeleteAnd i am not that stupid to think that Church didn't believe in the Trinity before the Creed or that it wasn't in the liturgy. Don't insult me.

I don't think anyone was insulting you, Marko, and I would not tolerate comments as such. I was using the Creed as an example of the liturgy already containing something latent in the Church before a formalization in doctrine or a formulaic, imposed understanding.

DeleteHis Grace John Michael Botean, DD, regarding the upcoming Thanksgiving Week.

ReplyDeleteIn view of the celebration of this civil holiday of Thanksgiving in the United States, I am granting a dispensation for all foods from Thursday through Sunday, provided one make a conscious, special act of gratitude to God for His many blessings before each meal, i.e., say a heartfelt prayer of grace. This holiday has become one of the few times families gather in our culture for a common meal, and I would like to encourage its celebration. The dispensation is extended throughout the weekend in order to prevent the temptation to the sin of gluttony or the wasting of food in a world of hunger. In view of this, I would also like to recommend that all our faithful commit to a special deed of charity as a sign of their recognition that "every good gift and every perfect grace" comes from our Father in heaven, and that His desire is that the goods of this world be shared by all.

A very blessed Thanksgiving feast to all -- and a blessed fast in preparation for the coming in the flesh of our Lord, God, and Savior, Jesus Christ.

+john michael

Since Pius XII has come up (again), I think it's worth pointing out Fr. Hunwicke's latest broadside on this front, just yesterday: "The process of liturgical 'reform' began before the Council; indeed, before the Pontificate of B Paul VI. The Begetter of the 'reform' was in fact Pius XII." http://liturgicalnotes.blogspot.com/2014/11/when-did-vatican-ii-liturgical-reforms.html

ReplyDeleteI would rather sar that the Begetter of liturgical destructions was Sarto=Pius X, when he destroyed the Roman Psalter and imposed a new one. But, since he is Tradistan's patrón, nobody even thinks of touching him.

DeleteK. e.

From what I've heard, he also had plans to set up a commission to work on the Roman missal as well.

DeleteThe difference is there seems to be no malice on the part of Sarto. As his Traddiness stated in an earlier post, there was an insane number of Double feastdays which took away from the liturgical season. Sarto's solution, however, was to change the psalter entirely instead of demoting a few saints to simple or ferial.

DeleteThe gardener needed to prune the tree; instead he cut off an entire limb.

With Pacelli, I'm not sure what his motivations were. They certainly don't look benign if he needed to cover his moves with a heretical pseudo-authoritative encyclical.

Lord of Bollocks,

Delete"The difference is there seems to be no malice on the part of Sarto."

True enough. More to the point, as someone in Fr H's combox noted, there also weren't the doctrinal problems with the Pian Psalter that there were with the various Bugnini led reforms. The Pius X Breviary may have been impoverished, and dubious in a number of respects, but it didn't reflect a modernist theology at work - just a regrettable ecclesiology and lack of respect for received tradition, one which would bear many far more bitter fruits in the coming century.

"The gardener needed to prune the tree; instead he cut off an entire limb." Well put.

Justinian,

ReplyDeleteActually, it appears that many folks in Fr. Hunwicke's (moderated) combox are more than willing to touch Papa Sarto's Psalter reform. And for that matter, the kindly host there has made his own pointed comments over the years.

It's pleasing to see that more and more of those of a traditional bent are willing to use a critical eye on what was done to the liturgy by 20th century pontiffs before 1958. By 2034 we might actually be getting somewhere.

We just need the Traditional/Orthodox Catholic demographic to gain numbers to gradually replace the Traditionalist Catholics. Those of the former come from a variety of backgrounds, whether it be Traditionalists who "got better" (like myself), Pauline Mass goers who discovered an interest in Tradition (like his Traddiness), the Anglican Ordinariates, or the Eastern Catholics.

DeleteLoB,

DeleteWell, as I have said before here, one of the positive aspects of post-2007 growth of traditionalism has been its increasing diversity, especially away from its old Econe locus...

The Ordinariates* and Eastern Catholics have their own problematic milieus. On the whole, however, I agree: they can and should be an essential part of a true restoration down the road.

* Too many Ordinariate priests use only the Novus Ordo, esp. in the UK. I'd love to see a motu proprio liberating all the ancient English rites and uses (Sarum, Hereford, York Bangor, Aberdeen, etc) for use by the Ordinariates and Anglican Use communities as a way of reconnecting with the roots of their own patrimony...heck, by all English-speaking Roman Rite priests, if I could dare hope for so much. I'm afraid that must await some future pontificate...

I heard from an Ordinariate priest that they are completely revising their book of prayer.

DeleteOne of the changes will include Rite II (basically the Novus Ordo) being eliminated as an option.

At least, so I hear.

LoB,

DeleteI'm in an Ordinariate community (NB: Canonically, there are as yet no parishes erected in the Ordinariate here in America), and I can clarify a little: the new Ordinariate Order of Mass (I have a copy) was disseminated for use beginning in Advent 2013, largely complete (some propers had not completed, such as those for Holy Week); basically, it was sent out in leather bound binders to the communities. It will be officially published in complete form in February, if there are no hiccups.

The Rite I/Rite II distinction was found in the old Book of Divine Worship, a strange and frustrating hybrid creation by Rome in 1983 for Anglican Use communities. Rite II was indeed the "contemporary language" alternative. It has indeed been eliminated in the new Ordinariate missal: "congregations wishing to use contemporary language are directed to use the Roman Missal, third edition, in the translation released in 2011." Which, unfortunately, some do, especially in England. But it is at least pleasing that contemporary language has been eliminated in the ordinariate missal itself.

Which is not say that there aren't Novus Ordo-type options in it if you want them. There are two Offertory options, for example - one drawn from the Anglican Missal tradition, the other reflecting post-Concliar usage. Likewise, there are two Eucharistic Prayer options - one is the Roman Canon, the other corresponds to EPII - though it is emphatic that the latter is not to be used for Sundays or Solemnities.

P.S. I'd like to single out the one sentence that forms a clear thesis in this essay: "I think a more prudent reply excludes the possibility that the pope, or any bishop, can create a new liturgy or discard large portions of the old liturgy."

ReplyDeleteSuch a proposition has never been formally part of the Magisterium, but it certainly seems to have been an implied understanding until the 20th century.

To both Athelstane and Lord of Bollocks:

ReplyDeleteDe internis neque Ecclesia. I don't know which were Sarto and Pacelli's intentions, but the fact is that the latter crimes would have never happened without the former's precedent. And, even if the new Psalter does not set theological problems, there is a hug liturgical (as Dobszay had pointed it) problem: that it is a rupture with the Roman tradition, and actually a novelty imposed without hesitation over the entire Latin Church. And all justified by ultramontanist views of Papacy.

On Sarto's liturgical reforms, I would distinguish between: 1) the Psalter demolition, a crime against God and His Church's Tradition; 2) the new Calendar, a better reform; 3) his "pastoral" decrees: frequent communion, reversal of the order of sacraments (first communion before confirmation), which seem to me to be wrong measures; and 3) the proposed general reform of Liturgy, which never happened - so we cannot judge it.

Such a proposition has never been formally part of the Magisterium, but it certainly seems to have been an implied understanding until the 20th century.

I also agree with it; and I reminds me what LoB said previously: he needed to cover his moves with a heretical pseudo-authoritative encyclical. I would agree on that since Pacelli reversed a traditional truth, he can be accused of heresy. But it is interesting that most Tradistanis deny this, because he didn’t oppose “a truth defined as a dogma”. This sentence, which is used often as a definition of heresy, seems to me a mere way of legitimizing innovations by presenting a whole part of Tradition (not formally defined infallibly) as a mere option which a future Pope could throw off.

K. e.

The "a truth defined as a dogma” loophole is particularly annoying. I'm sure there are a great many things in our faith that have never been "officially" defined as dogma, but that you'd unquestionably be a heretic to deny.

DeleteBut you are not Pacelli.

DeleteDeo Gratias

DeleteDear R.T. This post is true, good, and beautiful. M.J. is sending this link to everyone he knows.

ReplyDeleteYour ideas about the liturgy reveals a high quality soul. Thanks be to God that there are men like you in this crummy world.

May the Good Lord Keep you safe and productive for a long time