“These words prove the falseness of the apocryphal ravings.”

–St. Thomas Aquinas, paraphrasing St. Jerome

The

Proto-Gospel or Infancy Gospel of James is a highly relevant testimony to early Christian belief about St. Joseph. The authorship of this short narrative is contested, but most scholars seem to agree that it was composed in the second century A.D. under a pseudonym. The

Proto-Gospel ends with this claim of authorship: “And I, James, that wrote this history in Jerusalem, a commotion having arisen when Herod died, withdrew myself to the wilderness until the commotion in Jerusalem ceased” (24). Still, there is something to consider about the belief that this was written by St. James (presumably James the Just, not the early-martyred James the Greater). If this popular text had indeed been written by the hand of James, it would have doubtless been canonized into the New Testament with his epistle, but there is nothing to disprove its basis at least partially in an oral tradition from the apostle.

The apparent intent of the

Proto-Gospel is to tell a more fleshed-out version of the Nativity story from the Gospels, filling in a few gaps here and there, and making explicit narrative connections that could be only guessed at from the canonical accounts. Here, St. Joseph is a prominent character with much to do, as are Sts. Joachim and Zacharias. We learn about the birth not only of Christ, but of Mary, and we follow her childhood at some length. The names of her parents Joachim and Anna come to us through this document, and from no other known source. The belief that the Virgin’s parents miraculously conceived after many barren years—a belief attested to by numerous later mystics—also springs from these so-called apocryphal ravings.

The Narrative

|

| Joseph & Joachim |

As difficult as it is to skip over the stories of Joachim and Anna’s trials and of Zacharias’ martyrdom, Joseph is so important to the Jacobian narrative that his presence easily overpowers the others. When the priests assemble all the widowers of the land to present themselves as potential caretakers for the Virgin Mary (who has hitherto been living in the Temple up to her twelfth year), Joseph is so ready to obey that he “throw[s] away his axe” (9) immediately upon hearing the herald. When drawing lots between the widowers, Joseph’s staff is drawn last and miraculously produces a dove, which alights on his head. He immediately contests the call, for “I have children, and I am an old man, and she is a young girl. I am afraid lest I become a laughing-stock to the sons of Israel.” The priests threaten him with divine retribution if he continues to refuse an obvious call from Heaven, recalling the example of Korah’s rebellion against Moses. Joseph concedes the point, brings the betrothed girl to his house, and apparently leaves her there for almost four years while he leaves to build some houses, merely saying that while he is away, “The Lord will protect you.”

While Joseph is away on his construction projects, Mary has been chosen (again by lot) to spin the cloth for a new Temple veil. Noting that “at that time Zacharias was dumb” (10, cf. Luke 1:20), it falls to the priest Samuel to give instructions to the Virgin. While walking outside, Mary hears a voice saying the

Ave. Confused at seeing no speaker, she returns home to her purple cloth and is in the more iconographically correct pose of being seated when St. Gabriel appears to finish his message. When he leaves, she finishes her sewing quickly and absconds to Elizabeth’s house until her sixth month.

Then Joseph comes home. Mary is sixteen years old by now (12) and he is shocked to find her pregnant. He chastises himself first for his negligence: “I received her a virgin out of the temple of the Lord, and I have not watched over her” (13); immediately followed by a condemnation of her supposed unchastity: “Has not the history of Adam been repeated in me? The serpent came, and found Eve alone, and completely deceived her.” She insists on her own innocence, but seems unable to explain her fecundity, saying simply that “I do not know whence it is to me.”

What follows shows a subtle understanding of psychology that is lacking in many later commentators. Joseph’s troubling dilemma is expressed with a nuanced detail skipped over in St. Matthew’s Gospel:

And Joseph said: If I conceal her sin, I find myself fighting against the law of the Lord; and if I expose her to the sons of Israel, I am afraid lest that which is in her be from an angel, and I shall be found giving up innocent blood to the doom of death. What then shall I do with her? I will put her away from me secretly. (14)

Joseph does not simply assume that Mary is lying about her innocence, but nor is he certain she is not guilty. He has to cover both possibilities, and, recognizing the dangerous consequences of assuming either one, finds the safest middle ground in divorcing her quietly.

That night, the angel visits his dreams and corrects his errors. The next morning, a scribe friend arrives to say hello to the newly returned carpenter, but is horribly scandalized to find that Mary is pregnant before their marriage. The two are dragged to the priest and are made to endure an extensive ritual to prove their innocence, which they do just in time to receive the summons of the Roman census.

After some indecision about whether to enroll Mary as his wife or daughter, he enlists the help of two of his unnamed sons for the journey to Bethlehem. Once there, he leaves Mary with his sons and goes off to find a midwife, leading to this strange incident:

And I, Joseph, was walking, and was not walking; and I looked up into the sky, and saw the sky astonished; and I looked up to the pole of the heavens, and saw it standing, and the birds of the air keeping still. And those that were eating did not eat, and those that were rising did not carry it up, and those that were conveying anything to their mouths did not convey it; but the faces of all were looking upwards. (18)

Time stands still for St. Joseph. It seems plausible that part of the narrative is missing here, since the very next thing that happens is the appearance of the midwife walking over a hill. He explains himself and his strange marital situation to the woman as they walk back to the cave in which Christ is about to be born.

At this point Joseph nearly disappears from the narrative, and has little to do except act embarrassed at the midwife’s questions and meet the Magi when they arrive. There is not even a mention of the Flight to Egypt, and the Christ Child is hidden in an ox-stall when Herod sends out his army of late-term abortionists.

The Importance of the Proto-Gospel

The Jacobian portrait of St. Joseph is more subtle than one might expect. He is not the crotchety old man of the mediæval mystery plays, nor the balding and sexless youth of later plaster statuary. The Joseph of the

Proto-Gospel is stubborn but ultimately obedient, quick to anger but clever in prudence, practically minded but open to mystical experiences. In later retellings he would lose much of his nuance and become a more two-dimensional character. Some details would change over time as well, one notable example being the dove-sprouting staff which would become the more icon-friendly flowering staff.

St. Jerome took the slightest deviation from the scriptural text as a sign of doctrinal corruption. It is the rather benign addition of the midwife to the Nativity story which prompts him to condemn the “ravings of the apocryphal accounts” (

Against Helvidius, 10). With all due respect to this master theologian, his exclusionary scriptural minimalism leaves much to be desired. He and St. Augustine argued frequently about the proper interpretation of the Holy Writ, and Jerome famously desired to delete the so-called deuterocanonicals from the canon for rather pedantic reasons. The invective against “apocryphal ravings” has a rhetorical force that can be easily misused against the wrong targets.

If the claim that Joseph brought two of his sons to Bethlehem for the census (and perhaps for babysitting duties) is true, that would provide a reasonable substantiation that St. James was at least one source for this

Proto-Gospel. It is not beyond the realm of plausibility that James told his disciples in Jerusalem about incidents surrounding the Nativity which were not to be found in the already-written Synoptic Gospels. A few decades and a few embellishments later this account would finally be written down, and from there quickly copied and very widely distributed, if the large body of manuscript evidence is to be believed.

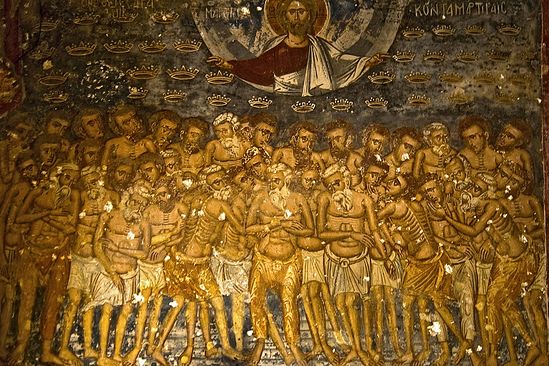

In the East, selections from the

Proto-Gospel are read at Mary’s feasts. In the West, it is so reviled that some even doubt the names of the Virgin’s parents given therein. See, for instance, the modernist nonsense posited in the 1914 Catholic Encyclopedia about

St. Anne. We ought to consider raising this text to a place of reverence again, even if not to the canon. The Jacobian narrative at least has the weight of liturgical and artistic tradition behind it, unlike the recent Josephite novelties.

Next Time:

A short survey of other early patristic-era texts, including the Gnostic gospels.

|

| St. James the Babysitter, pray for us! |