In a

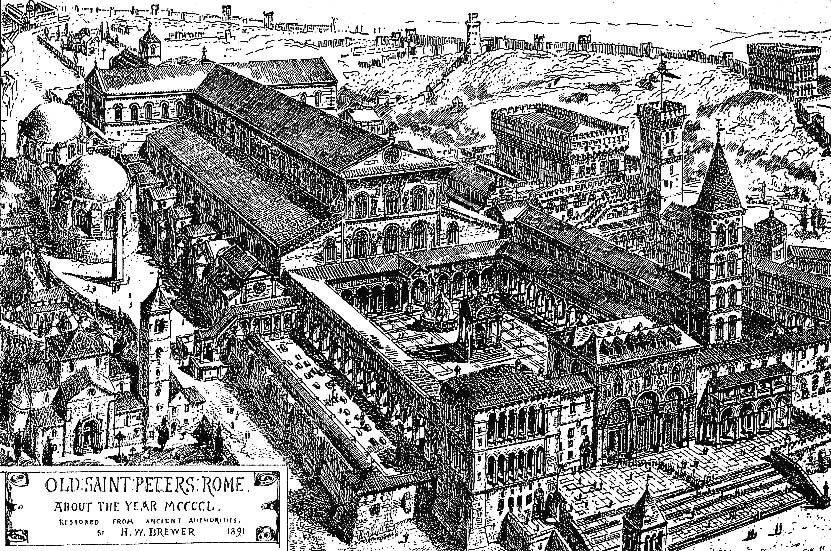

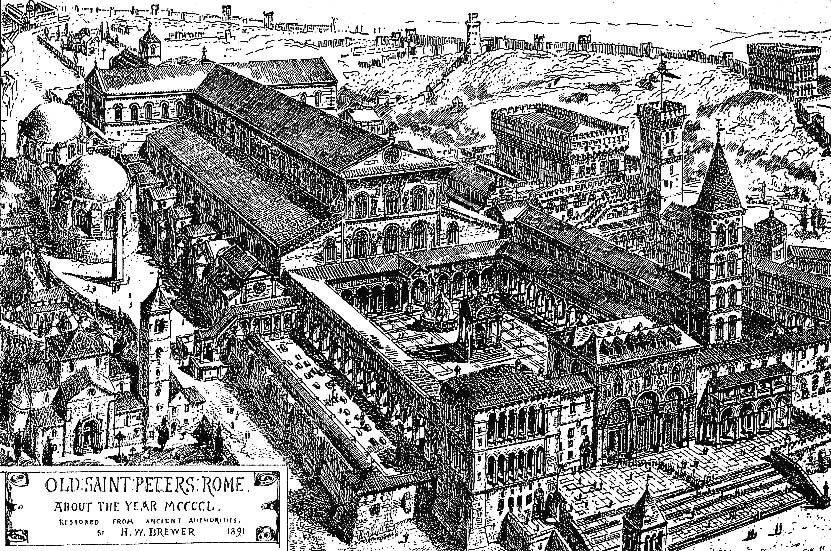

previous post we looked at the first millennium Roman liturgy from a textual and historical perspective, at how the traditional liturgy as we have it today evolved from a remarkably similar Mass around the year 800 AD. Today I just want to "throw" some material at you for your own edification once again, this time pertaining to the setting of the first millennium and medieval Roman liturgy, namely the original St. Peter's basilica. Most of what I have below is republished from last year, but with many improvements.

The original St. Peter's basilica was begun by Emperor Constantine over a shrine on Vatican Hill here Christians had venerated what tradition tells us was the place of St. Peter's burial since the first century—St. Peter's bones were not actually discovered until the reign of Pius XII. The basilica was completed in 360, but constantly remodeled. Originally the tomb of the first Pope of Rome was in the apse of the basilica, behind the altar. Tidal flow of pilgrims necessitated switching these two. A more elaborate throne for the Pope was constructed, as consecration of the Bishop of Rome became more usual at St. Peter's. The proliferation of Papal burials at St. Peter's and a series of ninth century invasions by Saracens necessitated further renovations. One such remodel, around the time of Leo IV, led to an altar embroidered in precious stones, ambos and doors of silver, and mosaics taken from the finest Eastern churches. Like most Roman basilicas, there was a group of canons attached to the church.

|

| from: bible-architecture.info |

A cloister preceded the entrance. I cannot help but think of Dr. Laurence Hemming's theory of the Catholic churches as temples, as fulfillment of the Temple of Jerusalem. The cloister here is more of an enclosed sacred courtyard than anything monastic. It functioned as a gathering place for people to prepare for Mass, an eschaton—a place between the world and eternity. A pineapple, which I believe predates the Christian era, sat at the center of the cloister. The faithful, as late as the eighth century, washed their hands for Communion at the fountains in this area—although reception on the hand differed drastically from the modern practice. In all, it is like the courtyards of the Temples of Solomon and Herod: a gateway through which the faithful would leave the world and prepare for the Divine. Sort of the story of salvation, eh?

|

Drawing of how the mosaics on the façade of the basilica,

as restored by Innocent III, would have been arranged.

source: chestofbooks.com |

The inside was very much that of a Roman basilica which, before the Christian age, just meant an indoor public gathering place for Romans. The nave would be lined with colonnade, but statuary and imagery was sparse and likely introduced in the early second millennium. The primary source of color would have been through patterns and mosaics on the ceiling, particularly in the apse. While Byzantine churches tend to either depict Christ as a child in our Lady's arms or Christ the Pantocrator in the apse, Roman churches vary more, and St. Peter's would have been no exception. St. Mary Major's apse bears Christ and our Lady seats in power, while the Lateran depicts Him ascended above all the saints—and above us, lest we forget, and St. Paul outside the Wall depicts Him in blessing but with a book of judgment. St. Peter's might have also had some variation of Christ in the apse, above the stationary Papal throne.

The altar was both ad orientem and versus populum, a rarity outside of Rome. During the Canon the faithful would go into the transepts and the aisles of the nave and face eastward with the priest, meaning they did not "see" the change on the altar. Curtains may have been drawn regardless, guaranteeing people did not see the consecration until the Middle Ages at least.

The populistic arrangement, of the Pope facing the people, gives us a clear indication of where the reformers discovered their "Mass as assembly" idea, but neglects the very hierarchical arrangement, which the Bishop of Rome elevated, surrounded by his counsel and the servants of the faithful in Holy Orders. Certainly a more popularly accessible structure than a Tridentine pontifical Mass from the throne, but not remotely as democratic as the reformers would have us believe. Papal Mass continued their arrangement through 1964, the year of the last Papal Mass.

|

St. Peter's basilica around the year 1450

(taken from wikipedia) |

Neglect during the Avignon papacy left the Roman basilicas in ruins, St. Peter's included. The roof of the basilica and its re-enforcement were both wood, which had long rotted. Instability eventually caused the walls and foundations to crack and, although many maintained the basilica was still usable, the decision was made to replace it in 1505 by Pope Julius II. The decision rightly sent Romans into uproar, as the old church had been used by the City and by saints for twelve centuries.

The fate of much of the original basilica is unknown. Elements of the portico survived, as did the Papal tombs. St. Peter's tomb received its own chapel, named for the Pope who built it. The high altar was retained and en-capsuled in the new altar. The altar sanctuary had been walled from the nave by winding pillars, supposedly taken from the Temple of Solomon. They were destroyed, although their design is retained in the new basilica's baldacchino.

Below is a reconstruction of how the sanctuary would have looked during the Middle Ages. Note the wall and doors, much like an iconostasis, betwixt the sanctuary and nave. The semi-circular benches around the Papal throne were for the canons of the basilica, the seven deacons of Rome, the archpriest, and the cardinals. The doors on the sides might have been either for the deacons, for those administering Holy Communion to the people in the transepts, or for those visiting the tomb below the sanctuary.

|

| From New Liturgical Movement |

Note the side altars, where the Roman low Mass as we know it was formed. Also, the entrance to St. Peter's tomb from doors under the stairs.

The reconstruction below, however, seems to aim at imitating a medieval version of St. Peter's basilica. The above image, of the basilica in the first millennium, shows a church which has not yet undergone various renovations consequent to medieval piety and style: the barrier above is more of a railing than a wall, there are side-chapels below but not above, and curtains around the altar—emphasizing the mystery of it all, and colonnade around the Papal throne—pointing to the unique place in the sanctuary of the chair of Peter. The walls are also sparser in the pre-Middle Ages image above. I suspect the person who created these images is of the Byzantine tradition, as he has put icons above the altars as decoration rather than more Romanesque mosaics and paintings. Still, quite an effort.

Below is a video from the same source showing a detailed view of the old basilica. I always found the old pineapple funny. It is a pagan bronze work dating to the first century and which resided in the Vatican square for no reason other than its pre-dating the basilica. The video is well worth your time and hopefully will engender some appreciation for the scale and Romanitas of the original church. Of course the details of the inside are mostly lost and would have taken the video's maker an eternity to construct.

Here is an account of the demolition of the original church:

From

Idle Speculations:

"At the beginning of Paul V.'s pontificate, there still stood untouched a considerable portion of the nave of the Constantinian basilica. It was separated from the new church by a wall put up by Paul III.

There likewise remained the extensive buildings situate in front of the basilica. The forecourt, flanked on the right by the house of the archpriest and on the right by the benediction loggia of three bays and the old belfry, formed an oblong square which had originally been surrounded by porticoes of Corinthian columns.

The lateral porticos, however, had had to make room for other buildings—those on the left for the oratory of the confraternity of the Blessed Sacrament built under Gregory XIII., and the house of the Cappella Giulia and the lower ministers of the church, and those on the right for the spacious palace of Innocent VIII.

In the middle of this square, at a small distance from the facade of the present basilica, stood the fountain (cantharus) erected either by Constantine or by his son Constantius, under a small dome supported by eight columns and surmounted by a colossal bronze cone which was believed to have been taken from the mausoleum of Hadrian.

From this court the eye contemplated the facade of old St. Peter's, resplendent with gold and vivid colours and completely covered with mosaics which had been restored in the sixteenth century, and crowned, in the centre, by a figure of Christ enthroned and giving His blessing.

To this image millions of devout pilgrims had gazed up during the centuries.

Internally the five-aisled basilica, with its forest of precious columns, was adorned with a wealth of altars, shrines and monuments of Popes and other ecclesiastical and secular dignitaries of every century. The roof consisted of open woodwork. The walls of the central nave, from the architrave upwards, displayed both in colour and in mosaic, scenes from Holy Scripture and the portraits of all the Popes.

It is easy to understand Paul V.'s hesitation to lay hands on a basilica so venerable by reason of the memories of a history of more than a thousand years, and endowed with so immense a wealth of sacred shrines and precious monuments.

On the other hand, the juxtaposition of two utterly heterogeneous buildings, the curious effect of which may be observed in the sketches of Marten van Heemskerk, could not be tolerated for ever. To this must be added the ruinous condition, already ascertained at the time of Nicholas V and Julius V., of the fourth century basilica a condition of which Paul V. himself speaks in some of his inscriptions as a notorious fact.

A most trustworthy contemporary, Jacopo Grimaldi, attests that the paintings on the South wall were almost unrecognizable owing to the crust of dust which stuck to them, whilst the opposite wall was leaning inwards.

Elsewhere also, even in the woodwork of the open roof, many damaged places were apparent. An earthquake could not have failed to turn the whole church into a heap of ruins.

An alarming occurrence came as a further warning to make haste. During a severe storm, in September, 1605, a huge marble block fell from a window near the altar of the Madonna della Colonna. Mass was being said at that altar at the time so that it seemed a miracle that no one was hurt.

Cardinal Pallotta, the archpriest of St. Peter's, pointed to this occurrence in the consistory of September 26th, 1605, in which he reported on the dilapidated condition of the basilica, basing himself on the reports of the experts.

As a sequel to a decision by the cardinalitial commission of September 17th, the Pope resolved to demolish the remaining part of the old basilica. At the same time he decreed that the various monuments and the relics of the Saints should be removed and preserved with the greatest care.' These injunctions were no doubt prompted by the strong opposition raised by the learned historian of the Church, Cardinal Baronius, against the demolition of a building which enshrined so many sacred and inspiring monuments of the history of the papacy. To Cardinal Pallotta was allotted the task of superintending the work of demolition.

Sestilio Mazucca, bishop of Alessano and Paolo Bizoni, both canons of St. Peter's, received pressing recommendations from Paul V. to watch over the monuments of the venerable sanctuary and to see to it that everything was accurately preserved for posterity by means of pictures and written accounts, especially the Lady Chapel of John VII., at the entrance to the basilica, which was entirely covered with mosaics, the ciborium with Veronica's handkerchief, the mosaics of Gregory XI on the facade and other ancient monuments. On the occasion of the translation of the sacred bodies and relics of Saints, protocols were to be drawn up and graves were only to be opened in presence of the clergy of the basilica. The bishop of Alessano was charged to superintend everything.

It must be regarded as a piece of particularly good fortune that in Jacopo Grimaldi (died January 7th, 1623) canon and keeper of the archives of the Chapter of St. Peter's, a man was found who thoroughly understood the past and who also possessed extensive technical knowledge. He made accurate drawings and sketches of the various monuments doomed to destruction.

The plan of the work of demolition, as drawn up in the architect's office, probably under Maderno's direction, comprised three tasks : viz. the opening of the Popes' graves and other sepulchral monuments as well as the reliquaries, and the translation of their contents ; then the demolition itself, in which every precaution was to be taken against a possible catastrophe ; thirdly, the preservation of all those objects which, out of reverence, were to be housed in the crypt—the so-called Vatican Grottos—or which were to be utilized in one way or another in the new structure.

As soon as the demolition had been decided upon, the work began.

On September 28th, Cardinal Pallotta transferred the Blessed Sacrament in solemn procession, accompanied by all the clergy of the basilica, into the new building where it was placed in the Cappella Gregoriana. Next the altar of the Apostles SS. Simon and Jude was deprived of its consecration with the ceremonies prescribed by the ritual ; the relics it had contained were translated into the new church, after which the altar was taken down. On October 11th, the tomb of Boniface VIII. was opened and on the 20th that of Boniface IV., close to the adjoining altar.

The following day witnessed the taking up of the bodies of SS. Processus and Martinianus. On October 30th, Paul V. inspected the work of demolition of the altars and ordered the erection of new ones so that the number of the seven privileged altars might be preserved.

On December 29th, 1605, the mortal remains of St. Gregory the Great were taken up with special solemnity, and on January 8th, 1606, they were translated into the Cappella Clementina. The same month also witnessed the demolition of the altar under which rested the bones of Leo IX., and that of the altar of the Holy Cross under which Paul I. had laid the body of St. Petronilla, in the year 757. Great pomp marked the translation of all these relics ; similar solemnity was observed on January 26th, at the translation of Veronica's handkerchief, the head of St. Andrew and the holy lance. These relics were temporarily kept, for greater safety, in the last room of the Chapter archives.

So many graves had now been opened in the floor that it became necessary to remove the earth to the rapidly growing rubbish heap near the Porta Angelica.

On February 8th, 1606, the dismantling of the roof began and on February 16th the great marble cross of the facade was taken down. Work proceeded with the utmost speed ; the Pope came down in person to urge the workmen to make haste. These visits convinced him of the decay of the venerable old basilica whose collapse had been predicted for the year 1609. The work proceeded with feverish rapidity—the labourers toiled even at night, by candle light.

The demolition of the walls began on March 29th ; their utter dilapidation now became apparent. The cause of this condition was subsequently ascertained ; the South wall and the columns that supported it, had been erected on the remains of Nero's race-course which were unable to bear indefinitely so heavy a weight.

In July, 1606, a committee was appointed which also included Jacopo Grimaldi. It was charged by the cardinalitial commission with the task of seeing to the preservation of the monuments of the Popes situate in the lateral aisles and in the central nave of the basilica. The grave of Innocent VIII. was opened on September 5th, after which the bones of Nicholas V., Urban VI., Innocent VII. and IX., Marcellus II. and Hadrian IV. were similarly raised and translated.

In May, 1607, the body of Leo the Great was found. Subsequently the remains of the second, third and fourth Leos were likewise found ; they were all enclosed in a magnificent marble sarcophagus. Paul V. came down on May 30th to venerate the relics of his holy predecessors

Meanwhile the discussions of the commission of Cardinals on the completion of the new building had also been concluded. They had lasted nearly two years"

[Pastor History of the Popes Volume 26 (trans Dom Ernest Graf OSB) (1937; London) pages 378-385]

The loss of the

original St. Peter's Basilica is a long forgotten misfortune for the Church. The current basilica is very impressive in all regards, and yet when

he visited it (a day after

seeing the Lateran and two days after seeing St. Mary Major) the Rad Trad found the current structure lacking in only one element: continuity with the past. The previous basilicas were truly Roman. And yet they have been updated with gothic flooring, Renaissance ceilings and paintings, baroque altars and décor, and even modern Holy Doors. The newer St. Peter's seems very much a standalone, quite apart from the other Papal churches in the City.

St. Peter's fell into neglect during the Avignon Papacy, when earthquakes could have their way with the Basilica and no Papal coffers proffered repair money. The wooden roof was similarly neglected. Upon return to Rome the Popes moved their major liturgical functions elsewhere and the deterioration worsened.

Perhaps some future oratory or cathedral, looking to maximize return without spending a load of money or choosing a brutally modern look, could go with the Roman basilica arrangement using St. Peter's as a model.

Some didactic

abstracts from a conference on the old basilica three years ago.

Lastly, here are some photographs I took while visiting the Petrine basilica three years ago:

Today is the feast of the Dedication of the Basilicas of Ss. Peter and Paul, two of the four patriarchal basilicas of the Roman Church. The current buildings are fairly recent (St. Peter's is a 16th century replacement of a 4th century basilica and St. Paul's is a 19th century reconstruction of the original, which burned and imploded). The Rad Trad did not get to St. Paul outside the Wall during his visit to Rome, but did manage to spend a full day in St. Peter's Basilica. The current building has very little to do with the one which preceded it, other than that it too houses the relics of the Prince of the Apostles.

I have re-posted some older material, a photo tour of the current basilica, for readers' edification. As stated on our previous post for the feast of the Dedication of the Lateran, these photos are perhaps better than what one will find online because they were taken during a progression through the church and hence give a clearer impression of the arrangement, scale, and style of the place. Some photos towards the end show the Rad Trad in personal horror (not a fan of heights).

The second lesson in the second nocturne of Mattins today seems to be based upon the fictitious Donation of Constantine (did Benedict XIV not want to rid us of this sort of thing?), but concludes with the interesting, and more historically feasible, statement that the consecration of a stone altar by St. Sylvester, Pope at the time, marked an official point of transition from wood to purely stone altars.

Happy feast!

Approach from the square

Sneak by the Swiss Guards

Our Lord watches this place

Where we hear "Habemus Papam"

Friends of the Rad Trad awaiting entry into the nave

First altar on the right is graced by the Pieta

Peering through the right-side door

A rather ugly statue of Pope Pius XII, among many statues of saints and popes

Looking back from the first chapel. This place is big! The current basilica

was built over the previous one, which too was the largest church in the world at

one point. The basilica's interior is a sixth of a mile long. I have sailed on large cruise ships

which would fit within this edifice comfortably.

A shot across to the altar of the Presentation

The baptismal font is enormous. Scale dominates this place

The dome over the baptistery

The coffered ceiling

Tomb of St. Pius X

The domes under the side chapels are quite colorful

The chapel of the choir, south of the high altar, which contains relics of St. John Chrysostom

Tomb of St. Gregory the Great. The Pope once vested for Solemn Mass here

while the schola sang terce

Apse of a transept

The baldacchino over the high altar is over 70 feet in height,

the largest piece of bronze work in the world

St. Andrew. There are many statues in the nave, but none of Apostles or Our Lady.

Those of the Apostles are to be found around the (ill-defined) sanctuary.

The entrance to the tomb of St. Peter and the Clementine chapel

St. Peter presiding at the basilica. A line of people wait to kiss his foot.

Confession in 22 languages from 7AM to 7PM

Looking from the altar to the nave

A friend of mine, who is over six feet tall, for size comparison

St. Gregory the Illuminator, disciple to Armenia

"I saw water flowing from the right side of the temple...."

The altar at the Petrine Throne with the Holy Ghost descending upon it.

It makes much more sense to see this during a Mass, which we did.

Saints watch and keep vigil

As we depart....

Later that day the Rad Trad visited the dome

The Rad Trad does not like heights

The Rad Trad really does not like heights.

Grabbing the cornice for dear life!

The Four Evangelists at the corners of the sanctuary

The inside of the dome

That ant below is a person! We were well over 200 feet above the floor

Friends delighting in the Rad Trad's fears

One last shot of the altar

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)