Octaves give the faithful seven days to digest a great feast. Rogation days, three days of penitential services and processions, precede the feast of the Ascension. St. Mamerus of Vienne instituted what eventually became the Rogation days while he was bishop of that see. The saint wanted his people to do penance so that they might repair for the wars of that region. The Council of Tours championed the practiced in 567 and in the ninth century it found a champion in St. Leo III, the pope of the age.

The Gospel of the Ascension and what occurs immediately after its reading are among the most subtle acts in the subdued Roman liturgy. In the 16th chapter of St. Mark's Gospel, Christ commands the Apostles to preach to the good news to the ends of the earth, telling them that they shall cast out devils, speak in new tongues, and survive poison, for no harm shall impede them from their charge. While this sounds hyperbolic, it means that the sign of the Church is miracles—God acting apart from conventional expectation to draw people's attention to the truth of Christ. If the sign of the Church is miracles, then the sign of the Church is holiness above all. Miracles are not part of the message of Christ or of the Church, rather they point to it and enable it.

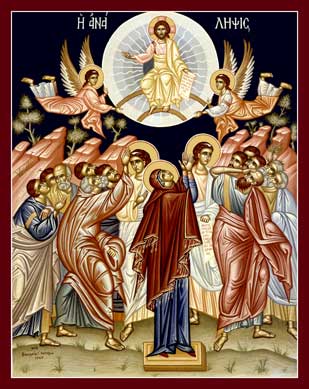

After the deacon has read the Gospel, an acolyte snuffs the Paschal candle, which will not burn again save for at the blessing of the font on the vigil of Pentecost. In the middle ages this act would have made more sense to us than it does in the 1962 form or the Pauline form (if it is still done). The other candles in a church would have been light from the Paschal fire, which burned without pause from Holy Saturday through the Ascension. Devotional candles, candles on side altars, and other candles in the sanctuary would have been lit from the Paschal candle before the acolyte extinguished it. Christ has taken the Apostles to the top of Mt. Olivet. Peaks of mountains and hills, as the "closest" point to heaven for those on earth and places of isolation, have special significance in the Scriptures. Moses ascended Mt. Sinai and received the Ten Commandments. Reflectively, Christ brought the Apostles up Mt. Tabor to show the congruity between the Jewish covenant and the one to come when He transfigured before them. At this moment atop Mt. Olivet, the Apostles again assume, again wrongly, that Christ will now restore the kingdom of Israel to its Davidic glory, forgetting the Lord's condemnation of Israel on Palm Sunday. A new covenant will be accompanied by a new Jerusalem, one based in heaven and present on earth, descending from one to another. God outwardly signified His presense in a cloud over the Mercy Seat on the Ark of the Covenant. Now, His presence would descend from heaven to earth and diffuse through the working of the Holy Spirit and the work of the Church, its opus Dei.

Saturday morning's Mattins delve more explicitly into the extinction of the Paschal candle. The Lord "has given us great and precious promises, that by [faith and knowledge (cf. 1-2)] you may be made partakers of the divine nature" (2 Peter 1:4). Grace is given freely, not seen instantly. It must be perceived by faith, just as the presence of Christ is no longer seen physically in human form, only by faith. St. Leo the Great explicitly states in the second nocturne of Saturday "the seen presence of Our Redeemer in the body has been changed for the unseen presence of sacraments, and hearing was given to the Church instead of seeing." As she can no longer "see" her Spouse, the Church turns to externals like the Holy Fire to as reminders of Christ's humanity and His perpetual presence. Some Greek churches expand beyond the medieval Roman practice by reserving the Holy Fire for the entire year and lighting all candles until the next Holy Saturday from it.

The Apostles are left at the peak of Mt. Olivet with the Virgin, confused and disconsolate, none the wiser than they were when Jesus said "The Son of Man must suffer" or "I go to My Father." For understanding they had to await the descent of the Holy Spirit. The Ascension of the second person of the Holy Trinity necessarily implicates the descent of the third. The first nocturne at Mattins on the octave day contains the greeting "peace from God the Father, and from Christ Jesus, the Son of the Father", stopping short of St. Paul's Trinitarian greeting in 2 Corinthians 13:14. As the Holy Spirit has not yet descended in liturgical time, the Church does not draw further attention to the Paraclete, only anticipation. Instead, she continues to focus on Christ's assumption of our humanity both at the Incarnation and the Ascension. St. Augustine of Hippo emphasizes in the second nocturne of Mattins that Christ had to be man for the Cross to matter and that he similarly had to God for the Resurrection to transpire. Local uses further expurgate on the communion between God and Man in the Ascension. The rite of Lyon, in the French tradition, offers additional readings at Mass within the octave. On Wednesday before the octave day the French church reads Christ's prayer: "I pray for them; I pray not for the world, but for them that you have given me, because they are yours. All things are yours and they are mine, and I am glorified in them" (John 17:9-10). The soul naturally drifts to the words recorded in Exodus 33:20, that "no man has seen my face and lived." Now that Christ has taken our humanity into heaven and left the promise of His divinity with us on earth, what was hopeless in the old covenant is now hoped for in the new. Adam fell and could not see God. Christ rose so that we may.

Saturday morning's Mattins delve more explicitly into the extinction of the Paschal candle. The Lord "has given us great and precious promises, that by [faith and knowledge (cf. 1-2)] you may be made partakers of the divine nature" (2 Peter 1:4). Grace is given freely, not seen instantly. It must be perceived by faith, just as the presence of Christ is no longer seen physically in human form, only by faith. St. Leo the Great explicitly states in the second nocturne of Saturday "the seen presence of Our Redeemer in the body has been changed for the unseen presence of sacraments, and hearing was given to the Church instead of seeing." As she can no longer "see" her Spouse, the Church turns to externals like the Holy Fire to as reminders of Christ's humanity and His perpetual presence. Some Greek churches expand beyond the medieval Roman practice by reserving the Holy Fire for the entire year and lighting all candles until the next Holy Saturday from it.

The Apostles are left at the peak of Mt. Olivet with the Virgin, confused and disconsolate, none the wiser than they were when Jesus said "The Son of Man must suffer" or "I go to My Father." For understanding they had to await the descent of the Holy Spirit. The Ascension of the second person of the Holy Trinity necessarily implicates the descent of the third. The first nocturne at Mattins on the octave day contains the greeting "peace from God the Father, and from Christ Jesus, the Son of the Father", stopping short of St. Paul's Trinitarian greeting in 2 Corinthians 13:14. As the Holy Spirit has not yet descended in liturgical time, the Church does not draw further attention to the Paraclete, only anticipation. Instead, she continues to focus on Christ's assumption of our humanity both at the Incarnation and the Ascension. St. Augustine of Hippo emphasizes in the second nocturne of Mattins that Christ had to be man for the Cross to matter and that he similarly had to God for the Resurrection to transpire. Local uses further expurgate on the communion between God and Man in the Ascension. The rite of Lyon, in the French tradition, offers additional readings at Mass within the octave. On Wednesday before the octave day the French church reads Christ's prayer: "I pray for them; I pray not for the world, but for them that you have given me, because they are yours. All things are yours and they are mine, and I am glorified in them" (John 17:9-10). The soul naturally drifts to the words recorded in Exodus 33:20, that "no man has seen my face and lived." Now that Christ has taken our humanity into heaven and left the promise of His divinity with us on earth, what was hopeless in the old covenant is now hoped for in the new. Adam fell and could not see God. Christ rose so that we may.

From that same state bear back

From whence by sin he fell,

To the joys of Paradise,

When Thou as Judge dost come

To doom the universe,

Grant, we beseech thee, Lord,

Eternal joys to us

In the Saints' blessed land,

In which we all to Thee

Shall Alleluias sing.

From the Sarum sequence for the feast

No comments:

Post a Comment