First, churches are dilapidated because they have been in continuous use with very little necessary maintenance since their original construction how ever many centuries ago. Her village, just outside of the capital, Yerevan, is supported by a monastic church built in 704. A neighboring church was built in the sixth century. While age is a prize, the churches are not kept to the degree that the similarly old Papal basilicas of Rome are. Armenia is poor and has always been poor. Also, during the many centuries when Armenia was under the yoke of the Muhammadans Ottomans and Soviets, church repair proved nigh impossible. The Armenian Church has traditionally valued austerity in style, but any minute ornamentation added over the generations has vanished into dusty grey and brown brick. One monastic church (shown in the video above) is fortunate to enjoy an on-going restoration; it was abandoned during the Soviet era, after Stalin's men threw the priests off the adjacent cliff one by one. Many churches are worse for the wear, but the more notable ones tend to inhabit natural features such as rocks and caves, which lessens the concern for their decay.

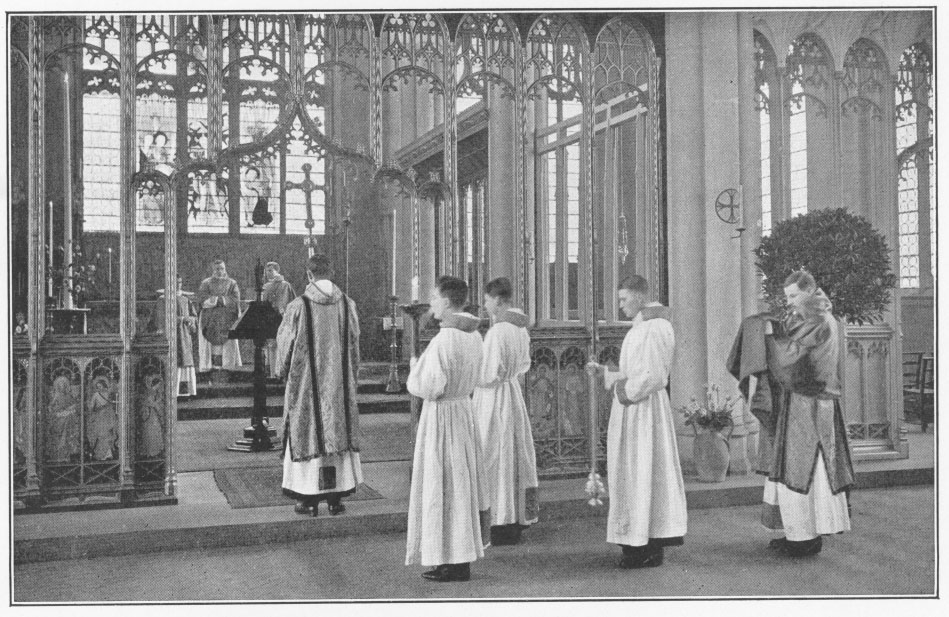

Second, the churches are still well attended and occupy a place of importance in the community. In the villages women wear veils—not doilies and mantillas, real veils—whenever they enter the church, even to light a candle; in Yerevan, they veil solely for Communion, as they do at St. Vartan Cathedral in New York. The Mass (as most English-speaking Armenians call their Eucharistic sacrifice) and the Office are conducted in Old Armenian, which is less intelligible to an Armenian speaker than Slavonic to a Russian or Ukrainian and with an air of mystery, covering the altar with a curtain during the introductory part of the liturgy. Sermons are rare outside of the cathedrals; priests may deliver a short fervorino, but formal homilies are the realm of the bishop. They just "get on with the Mass" I am told. As there are no real sermons there are no real seats, that Protestant innovation for listening to ecclesiastical lecturers drone. The altar remains the singular point of focus. The faithful do not turn their backs to the altar at any point and leave the church walking backwards. Little has changed in devotion, although Ottoman and Soviet rule have driven change in popular religiosity.

Lastly, the priest may not sermonize, but he is still a person of importance in town. They do not limit their communal role to the church, which is available for all. They enjoy the status of a reputable person whose opinion should be heard but whose power is not firm, not unlike a former mayor would be in Western countries.

The collapse of the Soviet Union, more than the communist empire itself, wrought tremendous poverty in Armenia. The population of that country is a fraction of its diaspora, although both numbers are falling quickly as Armenians abroad marry men and women of other ethnicities. Those who remained after the post-Soviet fallout tended to be those incapable of escape, people who did not go through much education and who continue to live agrarian lives. They retain their culture and social structure much as they did years ago, if without the kindness they once did; poverty is so pervasive that "They look as if they can't wait to die."

Armenia was the first country to proclaim Christianity its formal religion, before Constantine even held the Roman Empire and centuries before St. Vladimir or Charlemagne. In your charity, consider offering a prayer for the spiritual children of St. Gregory the Illuminator.