|

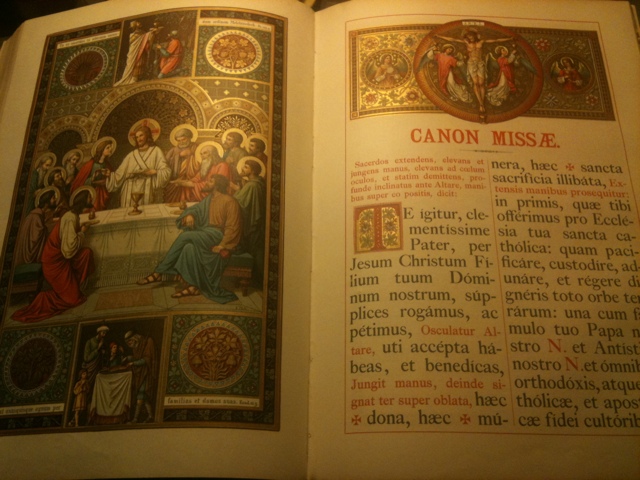

The Ambrosian rite of Mass, a Latin liturgy dating to ancient times and

which is independent of the Roman rite.

source: New Liturgical Movement |

When I first read Gregory Dix's

Shape of the Liturgy I was struck by St Hippolytus's description of the primitive liturgical rites (a description which unfortunately gave rise to a curious new Eucharistic prayer in the new Roman Mass) as well as Dix's own description of the Liturgy of Addai and Mari, which contains no words of institution ("this is my body" and "this is my blood") and has a very passive epiclesis compared to the Liturgy of St John Chrysostom. This torn down the temple veil and gave my the first insight into a different way of thinking, one where theology derives from liturgy, as it was in Rome until the time of Trent, rather than the other way around.

The liturgy, properly done, originates in an Apostolic church and reflects the prayer life and faith of that community. In the ancient Roman rite many of the collects reflected a grim outlook on life, an emphasis on the temporal punishments for sin and the need for repentance and forgiveness. Similarly, the congregational parts of the old Roman rite are in many ways a continuation of how Romans would behave either in the presence of the emperor or in large public assemblies. In short, the Romans prayed as Romans, the Byzantines as Byzantines, the Armenians as Armenians, the Irish as Irish and so forth.

Liturgical prayer unfolds the mystery of God before the eyes of those who pray and illuminates those mysteries according to their understanding. The Eucharistic rites and the Office should then be a tremendous source of reflection, rumination, meditation, and theology. The psalm antiphons in the old Roman office are themselves an occasion for prayer, particularly the antiphons for the octave of Christmas.

|

The Addai and Mari rite, scourge of Scholastics

source: St. Mary's Cathedral, Kochi |

Once I shared with an aspiring Dominican friar this observation. The example of liturgy as something revealed which I adduced was the aforementioned rite of Addai and Mari, which breaks with the standing tradition East and West by not having an institution narrative. Similarly, many ancient recordings of the Eucharist neglect the narrative, although these accounts may be very general descriptions rather than actual texts. My friend went into a Thomistic fit! The theology of St Thomas Aquinas, mainstream for centuries but formally canonized at the Council of Trent, holds that consecration occurs at the words "this is my body" and "this is my blood." How could a Eucharist be valid otherwise? The reality of the matter is that this rite is valid whether particular theological traditions hold it to be or not; the Church has said it is valid; the constant use of this rite since the third century gives it precedent over particular theological analyses. Even in Part III, Question 78 of his Summa St Thomas acknowledges that his analysis is based on the Roman form of consecration, implying some limits to what he says. Adopting a Romanesque theology from the Middle Ages and applying it to a third century Assyrian rite is quite absurd!

In short, let us receive our liturgical traditions and faith from our God-fearing fathers with reverence and not tinker with them so that they may be to conform to a particular model. Should we do such a thing, we may be left with very little of value.

A good example of a "received" bit of liturgy is this "collect" from the old Mass of the Assumption of Our Lady:

Forgive, O Lord, we beseech thee, the sins of thy servants: that we who by our own deeds are unable to please thee, may be saved by the intercession of the Mother of thy Son our Lord.

This prayer is subtle and meek. Compare it to this dogmatic, heavily-laden prayer written in 1950 after Pope Pius XII used Papal Infallibility to define the Assumption of Mary:

Almighty, everlasting God, Who took up, body and soul, the immaculate Virgin Mary, Mother of Your Son, into heavenly glory, grant, we beseech You, that, always devoting ourselves to heavenly things, we may be found worthy to share in her glory.