Today is the feast of the dedication of the Cathedral of Our Savior, commonly known as the Archbasilica of St. John Lateran, the cathedral of the diocese of Rome and hence the foremost Church in the world. The cathedral has probably been re-built half a dozen times due to fires, earthquakes, and the Avignon papacy, yet some of the original building remains, which traces its origins to the Emperor Constantine. I had re-published an old post showing some pictures I took of the Cathedral during my visit there a few years ago. I think this better than posting images available from the internet because the display the "flow" of the cathedral and lend themselves to an appreciation of the look and scale. At the end I have added a video of the consecration of the FSSP seminary chapel in Nebraska which, although done to the 1962 rite, is textually very close to how the Mass part of the rites would have been done at the Lateran during its several re-consecrations. Happy feast!—one of my favorite of the year.

|

| The image of Christ dominates this great cathedral built in His name |

The Archbasilica of Our Savior has also been known as St. John Lateran since Sergius III re-consecrated the building once, adding the patronage of the Evangelist and the Beloved Apostle; the primary patronal feast is the Ascension of Our Lord Jesus Christ. This church is great not so much for its size, grandeur, history, or architecture—although all are quite impressive, but because this church is the cathedral of Rome and, hence, the foremost church in the world. It is the Pope's cathedral, although people often mistake St. Peter's for this honor.

|

| The throne of the Bishop of Rome |

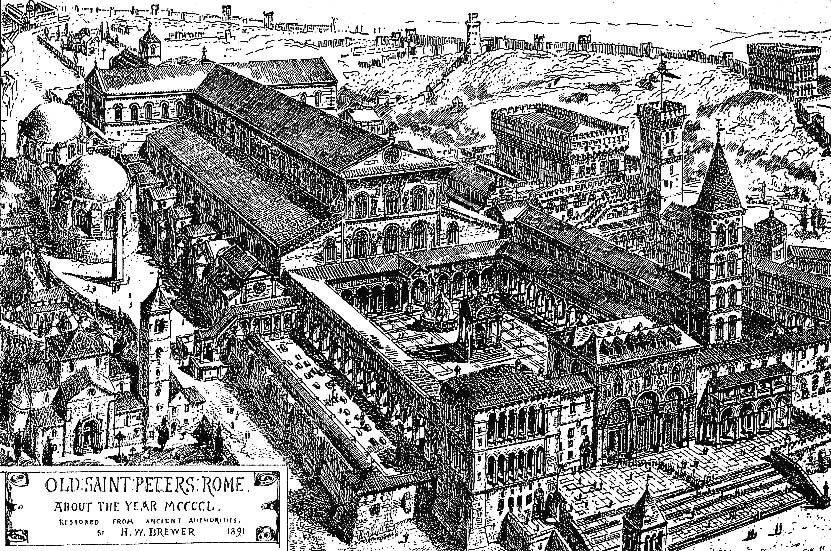

Christian worship existed at this location in the southeastern corner of Rome, near the walls of the old City, since the first century, when Ss. Peter and Paul themselves were present there. After Christianity was permitted to crawl out of the Roman woodwork Emperor Constantine began to build several major churches on behalf of the Christians. Contrary to popular opinion, Constantine did not give too much preference to Christianity over paganism during this period. He gave the Church and the Bishop of Rome considerable real estate, like the Lateran Palace, where the popes resided until the reign of Pius IX, but not in prime locations.

The Church of Our Savior eventually became the main seat of the Bishop of Rome due to its proximity to the Lateran Palace. Important stational days during Holy Week—particularly Palm Sunday, Maundy Thursday, and Holy Saturday—which are communal in nature take place here. The consecration of the Bishop of Rome, and his coronation as Pope, and special blessings took place at this cathedral, emphasizing the Pope's role as a bishop for the City. During one Maundy Thursday Pope St. Gregory the Great was performing the mandatum (re: foot-washing ceremony) and after washing twelve men's feet and thirteenth appeared. This man's luminous face was described as perfect by the Pope. The man immediately disappeared. St. Gregory concluded it was an angel, or perhaps even Our Lord Himself. This is why in the old Roman rite thirteen men's feet were washed in Maundy Thursday as opposed to the instinctive twelve.

The Cathedral of Our Savior was subjected to barbaric invasions by the Goths in the sixth century, by the Saracens in the ninth century, and earth quakes throughout. By the reign of Sergius III (r. 904-911) the Cathedral had fallen into such disarray it required a re-model, including a new roof. It was re-dedicated by Pope Sergius and given a consecration to Ss. John the Baptist and John the Evangelist, hence its vulgar name "St. John Lateran."

|

| The Lateran Cathedral as seen from the square |

In the first millennium the square in front of the Lateran Cathedral and Palace hosted the election of the Pope. After the death of the previous Pontiff the clergy would gather all Roman citizens, the cardinals (originally the priests and deacons of Rome) would elect nominees from among themselves, and the candidate with the greatest yell from the crowd would be the new Bishop of Rome. In the late first millennium violence often resulted and which faction could gain entrance to the Cathedral, consecrate its candidate, and enthrone him would have the Pope! During the middle ages the Archbasilica hosted five ecumenical councils, the Papal Court, and the public square of Rome. Pope Innocent III famously received St Francis of Assisi here, after first suggesting that the poor saint preach to the pigs in the public market—a suggestion which the saint immediately followed, and also saw the friar holding up the Cathedral, which was crumbling under the sins of the Church.

|

| Pope Benedict XVI enthroned after election |

As the Popes moved to Avignon, the Cathedral fell again into disarray and was partially destroyed due to a fire. It was re-modeled during the Renaissance and again during the 18th century, when the statues in the niches were added. Today the Popes still use this great Cathedral for Maundy Thursday, Ascension Thursday, Corpus Christi, pastoral visits, and enthronement after election.

I was blessed by God to be able to visit this awesome place a year and a half ago, whilst in Rome during Lent. My two friends and I, one Catholic and one then-searching, thought the Lateran to be an interesting one hour stop we could make on our way to the Colosseum. We spent five hours in the Lateran and two in the Colosseum.

The facade, a baroque addition, is impressive, but not as impressive as the one gracing St. Mary Major. I was not impressed with the Lateran until I stepped inside. What first struck me was the sheer scale of the place. I have been to St. Patrick's Cathedral in New York City several times, a larger church, but less open and hence smaller in scale.

|

| The imposing Cosmatesque floor |

My feet were sore from walking the Eternal City in boating shoes, so I ended up dragging the pads of my feet without intending to do so. This had the most spectacular effect. One can

feel the texture of the mosaic floor in this Cathedral. Every bump and tile has character to it. History seeps from the ground of this place and the Spirit of God encompasses it. The words of the introit are verily said of this house of God:

Terrible is this place and This is none other than the house of God; this is the gate of heaven; and it shall be called the court of God.—Genesis 28:17

We made our way through the various side chapels over the course of an hour or two, before coming to the Chapel of St. Francis of Assisi, shown below. The five piercings on the heart held by the angel simultaneously recall the stigmata of St. Francis and the devotion to the Five Wounds, popular during Francis's time.

The Blessed Sacrament Chapel is next to the Papal Altar. There is a grand tabernacle surrounded by four statues of Popes and crowned with an ethereal image of the patronal feast, the Ascension of Our Lord Jesus Christ. Interestingly the Popes are vested as deacons, indicating that they too are just servants at the altar of the High Priest, Christ. May his holiness, Francis, wear the pontifical dalmatic and find himself in the same self-effacing service as past pontiffs.

In the center of the Cathedral is the Papal Altar, topped by a canopy and reliquary which, although ornamented with busts of St. John the Baptist and John the Evangelist, contains the head of St. Paul. Imagine that almost every Pope from the fourth century has celebrated Mass in this place, surrounded by St. Paul and Our Lord Himself.

|

| The Papal Altar |

And the ciborium with the reliquary:

Across from the altar is the great apse of the Cathedral. A massive back wall is topped with gold mosaics containing icons of Our Lord, Our Lady, Ss. John the Baptist and John the Evangelist, and other Biblical figures. One must also recall the organic continuity of this cathedral. Icons of Ss. Francis and Dominic were not-so-deftly inserted at a later time! At the end of a long aisle, containing an organ, balconies for the cantors, and choir stalls for clergy in attendance, is the throne of the Supreme Pontiff:

Beyond the apse is a gift shop. Horrifically, the tomb of Pope Innocent III, the most powerful man of the Middle Ages, is a cross beam for the door frame! How passes the glory of the world!

Something striking about this place is the color in it. The nave is a bland white, as per Italian baroque style for public places, but the sanctuary and other locations from the early Christian era, Middle Ages, and Renaissance is thriving with life and color. Even niches between icons and mosaics were treated as opportunities to paint images, images which literally pop out into a third dimension:

The nave for contrast:

The layout is distinctly Roman, the floor is medieval, the ceiling Renaissance, the chapels Baroque, and place entirely Catholic.

|

| The ceiling is a wonder |

The Cathedral's altars, chapels, aisles, and niches are a testament to the on-going effort that is the Gospel of Christ, one held by sinners and saints, which must endure every trial and be maintained and expressed through every age. This aisle towards the entrance contained numerous chapels under renovation.

I will leave on a light note. One of my companions was quite taken with the statues of the twelve Apostles in the nave, which are gargantuan in this size given the scale of the Cathedral. Upon arriving at St. Matthew, my friend decided that since the former tax-collector no longer needed his gold, there was no excuse to let is sit unused.

|

| Gimme! |

Lastly, across from the Lateran Cathedral is the

Scala Sancta, the Holy Stairs from Pilate's palace. Christ was tried atop these steps and descended them to take up His Cross for us. One may only ascend these steps on one's knees. More on them another time....

VIDEO:

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)