|

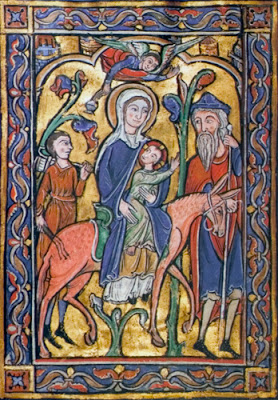

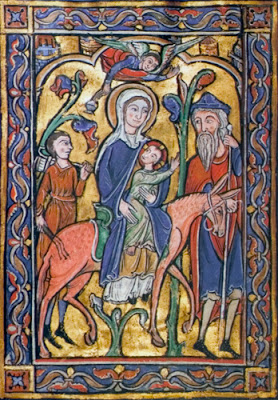

| (Poussay Gospel Book) |

Joseph of Nazareth matters because he was a great saint. As the Virgin’s Betrothed, and as one who lived at least a couple of decades in the immediate presence of the Incarnate Word, it is implausible that Joseph did not finally die as a holy and contemplative man. Since St. Joseph has been named Patron of the Universal Church, and since recent popes have called for a greater devotion to Joseph, let me propose a hagiographical alternative to the more common Josephite ways of thinking about his life.

The Life of Joseph

Born into the lineage of David, but one of a large and poor clan, Joseph’s royal heritage offered him little but a memory of Israel’s lost greatness. (I offer no solution here to the question of whether the lineages listed by Sts. Matthew and Luke are Joseph’s or Mary’s; even the Fathers could not decide on that.) He was a man of humble means, and had to work as a carpenter and builder for a living. His artisanship may not have been magnificent, but it was sturdy and solid.

He married at the normal age for a Jew of the time, and fathered a reasonably-sized family. He was a pious man, keeping all the Hebrew holy days, praying the psalms, and studying the Law as much as his state in life allowed. He was a just man, not known for dealing poorly with his neighbors or his patrons. His wife—possibly named Melcha, Escha, or Salome—died only after bearing him sons and daughters, maybe even after they had grown and married, themselves.

As he grew older and watched his family increase, he anticipated a venerable old age. As the Proverbs say, “Youth has strong arms to boast of, old age white hairs for a crown.” His sons gradually took over the family trade, with Joseph a frequent presence as mentor and occasional worker. He taught his sons how to deal justly in their business and in their family life.

And then one day he was called to Jerusalem with his unmarried kinsmen for some confused purpose. Suddenly the priest began casting lots, Joseph’s staff miraculously produced a dove, and he found himself as the caretaker of a young Temple virgin.

Much to his chagrin and to the chuckles of his kinsmen, he brought the girl and her companions home to Nazareth. He left her there while he went to oversee a building project, and returned to find her pregnant with a strange story about an angelic visitation. Perhaps he had heard rumor of the angel who came to visit the priest Zachary concerning his own aged wife’s miraculous pregnancy. He did not wish to think poorly of the girl, but still found her story hard to believe, and began weighing his options. Before he could decide on a quiet divorce, the angel appeared to him in a dream and told him that the Child was of God.

Suddenly he began living in a whirlwind of activity with which he could scarcely keep pace. He had to travel from Nazareth to Bethlehem, from there to Egypt, and finally back to Nazareth. During those travels he witnessed numerous miracles of all kinds, and met men from many nations and walks of life. By the time he returned home with his young wife and her toddling Son, he had seen wonders beyond those shown to the greatest of prophets.

Then, there were the quiet years in which he returned to his life of work and prayer, perhaps still mentoring his sons and his grandsons in their carpentry. The Incarnate Word came along to the family carpentry shop and was the cause of some wonder to the rest of the clan—this strange young Boy who had vanished with Old Joseph for a few years into the south amid stories of Herodian terrors. Perhaps one day James Bar-Joseph was indeed healed from a viper’s attack by the Christ Child while working amongst the builders.

The enigmatic episode at the Boy’s twelfth Passover reminded Joseph that Jesus was destined for a messianic role, and perhaps he wondered if he would live to see its fruition. As Jesus matured into manhood, Joseph grew ill and felt death approaching. Confessing his sins to the Man all others believed to be his son, and begging the forgiveness of the wife whom he had doubted, he was given the grace to pass out of this life in the presence of the New Adam and the New Eve, the first-fruits of their spiritual union. His soul was carried by the Archangel Michael, guardian of Israel, to the

limbus patrum.

Such was the life of old St. Joseph.

Symbolism & Typology

Joseph was in a sense the last patriarch—that most Hebrew of roles—and symbolized the bridge between the Old Covenant and the New. He lived almost uniquely through two eras, and served as a patriarch in the old sense (by the fathering of children) and in the new (by celibate spiritual fatherhood). He was both a sinner and a just man; even the just man falls seven times only to rise again.

The dream of the ancient Joseph might also be seen as a prophecy of the latter Joseph’s role: “In this dream of mine it seemed to me that the sun and the moon and eleven stars did reverence to me” (Gen. 37). The cosmic parallels to the Woman Clothed with the Sun are hard to ignore: “A woman that wore the sun for her mantle, with the moon under her feet, and a crown of twelve stars about her head” (Apoc. 12). One also wonders about her wings—“there were given to the woman two wings of a great eagle, that she might fly into the desert”—and whether the assistance of St. Joseph during the Flight into Egypt might not here be figured.

As Israel of old confused his son Joseph by blessing the older Manasses with his left hand and the younger Ephraim with his right, so did the youngest “son” of the new Joseph exceed the elder brethren in blessing: “But this younger brother shall be greater than he, and his seed shall grow into nations” (Gen. 48).

Just as Joshua (Jesus) of old escorted the bones of Joseph into Shechem of the Promised Land, so did the new Joshua escort the soul of his foster-father into Paradise along with the long train of blessed souls at the Ascension.

Iconographically, Joseph is most properly depicted with a pair of doves or a flowering staff rather than a carpentry square. Usually he is shown with Mary and the Christ Child, but physically distanced from her to symbolize their chaste relationship. Common themes are the Nativity, the Presentation, the Dream, and the Flight into Egypt.

Next time, we finally conclude our series on St. Joseph.

|

| St. Joseph, dreamer of dreams, pray for us! |