I am grateful to the St. Lawrence Press for the opportunity to review their Ordo Recitandi Officii Divini Sacrique Peragendi for 2015, as well as for the time spent by the compiler, Rubricarius, to answer questions about the history of the Ordo, provide us with some invaluable history told from experience, and his thoughts on the future of the traditional Roman liturgy. I have never looked at an Ordo other than a quick glance at the FSSPX one while at the Oxford Oratory (more accurate than the LMS), so I cannot compare the St. Lawrence Press version's quality to other ordines, but I think the thoughtful layout and the efficient presentation will speak for themselves. This booklet, which continues the praxis of the early traditionalists in following the 1939 typical edition of the Missal, should be helpful for all gradations of use: laymen, solitary priests, and for public prayer settings. Even non-users might find the Ordo an interesting study in the traditional liturgy's kalendar and commemoration system, although this booklet does deserve to be put to practice.

Part I: Reviewing the Ordo

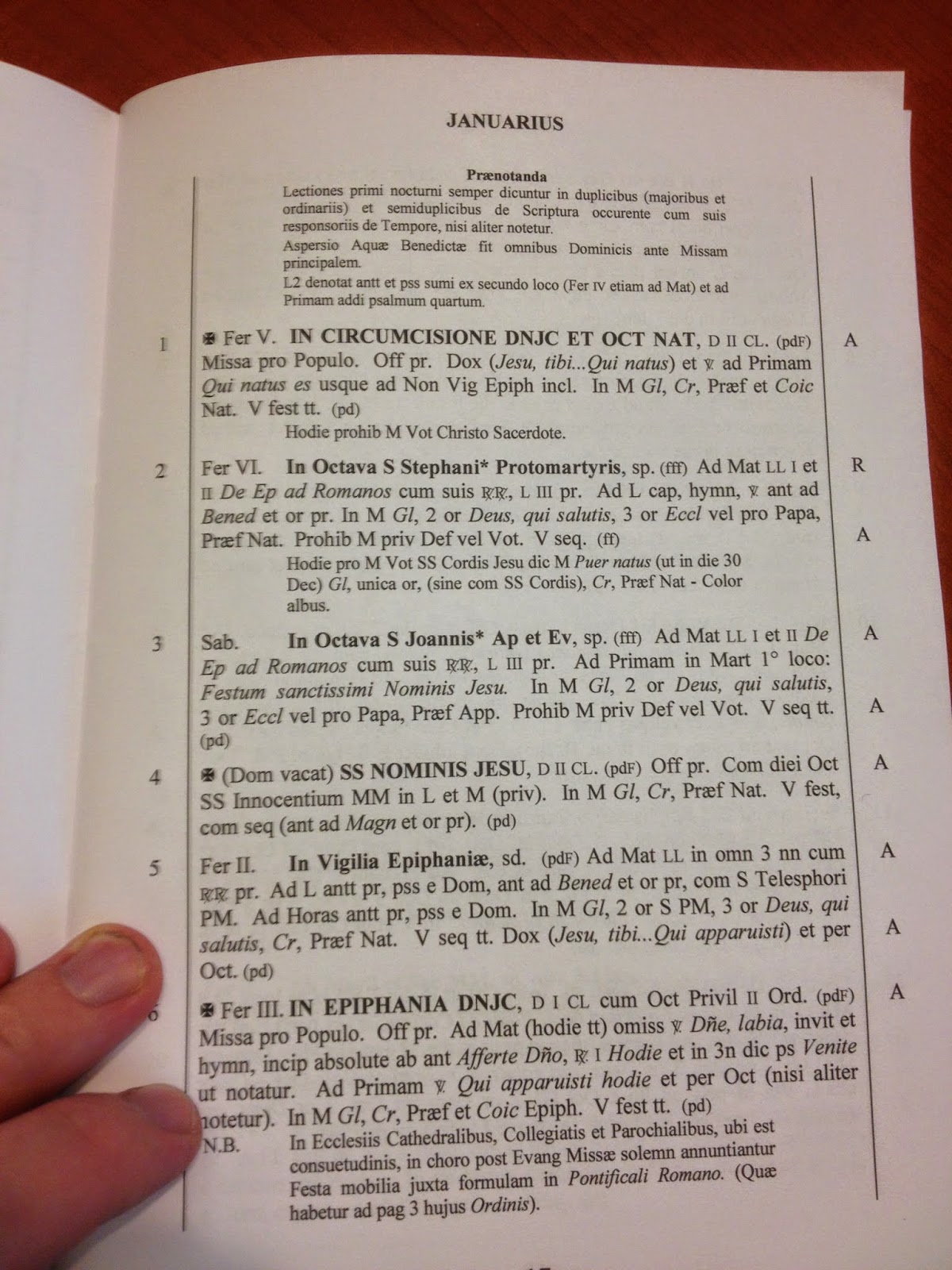

The first page contains immediately useful information on the dates of the variable feasts of the year and the four sets of ember days. Atop the third page is the proclamation of the variable feasts sung after the Gospel every year on the feast of the Epiphany, which would be helpful to someone working without a form.

The Ordo, which is entirely in Latin—no Classical word flourishes, mercifully—publishes exhaustive, straight forward, and concise details on such things as external solemnities, titular feasts and the dedication of churches, private and public votive Masses—normal and Requiem, and the guidelines for the Forty Hours devotion, which, despite being eleven paragraphs long, is quite simple and more thorough than what one finds in Fortescue.

Yes, there can be an external solemnity of the Sacred Heart. The rubrics on the left continue the extensive directions for the Forty Hours.

The rules around Masses for the Dead vary in strictness depending on whether or not the Mass is a sung Mass or not. This Ordo forgets not the finer details of the commemoration system, too, such as the use of the orations for the dead on the first feria of the month at Mass.

When I first heard that the Last Gospel is replaced with another text on some days, I was a bit confused when told that this only occurs when the displaced text is "strictly proper." The Ordo contains a very good explanation that any priest should be able to remember and understand when consulting the Ordo listing for a feast or Sunday which displaces another day.

Guidelines for orations, the Ordinary of Mass, and prefaces in private votive Masses, which differs in many respects from 1962.

In order to be succinct, the Ordo does not give long explanations like the LMS and FSSPX ordines, but instead employs an abbreviation system. At first all these potential entries look intimidating, but the layout of the pages containing the liturgical orders of the days makes everything more intelligible.

For example, the R next to the octave day of St. Stephen indicates that the Mass and Office of the day are observed in red vestments and with a red altar frontal. The A midway through the entry directs a change to white (albus) for V seq (Vespers of the following day).

I believe most ordines begin at Advent. The St. Lawrence Press Ordo begins with January 2015 and, considerately, runs to the 10th of January, 2016.

This page is a nice example both of the clarity of the Ordo and the depth of the old Roman rite. The page is for March. The 23rd is a Lenten Monday which, noted by the X to the right, permits a votive Requiem Mass (as do all ferial Mondays of Lent). At Vespers the color changes to white for the feast of St. Gabriel the Archangel, a greater-double feast. At Mattins, the lessons and responsories in the first nocturne are proper to the feast. The ninth lesson is that of the displaced feria. The feria is commemorated with its Benedictus antiphon and collect at Lauds, as well as with a commemoration and proper Last Gospel at Mass (it is strictly proper). A private Mass may be celebrated of the feria with a commemoration of St. Gabriel and a proper Last Gospel, the prayer super populum per the Lenten feria, and the Benedicamus Domino dismissal, all done in violet for the Mass alone. Vespers is of the following feast of the Annunciation, a double of the first class, with the Incarnation doxology used in the hymns that night and during the hours on the 25th.

Certain days, such as those of the Triduum, contain long descriptions of unique rites and ceremonies proper to the day. Any church master of ceremonies would already be expected to know this information, but I suspect it would be a very helpful reminder to the sacristan, who might read it over to remember everything he needs to prepare the altar, the vestments, and any other articles necessary for the day. A thoughtful sacristan might even read ahead and ask the priest if he anticipated celebrating a votive Mass or a ferial Lenten day on a feast and then write an emendation in the generous margins.

This is an excellent Ordo for use and study by both clerics and laymen. I would recommend getting a copy yourself and putting it to some good use. To order the St. Lawrence Press Ordo for 2015, click here. They take PayPal.

Part II: Interview with the Compiler

Herein follows an interview with Rubricarius, the compiler of the Ordo and friend of this blog. He gives us some history about the Ordo as well as some very unique views of the future of the old rite and about Summorum Pontificum which should get the comment box rolling.

A. If I may answer these questions together Rad Trad? As I mentioned earlier it was actually the

$$XP itself that was publishing the Ordo

from 1979 onwards with a considerable number of its clergy using it. When the trustees of the St. Pius V

Association had handed over its assets to the $$PX one of the conditions was

that the pre-Pius XII liturgy was to continue to be used. I understand that one of the original

trustees deeply regrets now not having taken legal action when the $$PX reneged

on the terms. Who knows what might have

been... Anyway, as to the ukase to

enforce the use of the 1962 books this was a consequence of discussions

Lefebvre was having with Rome in the early 1980s. I have letters from both Michael Davies and

Bishop Donald Sanborn – from opposite ends of the Traddieland spectrum - confirming

this to be the case. In his letter

Michael Davies states that the indult Quattuor

abhinc annos was a direct consequence of these discussions. (We can see the

parallels with Summorum Pontificum

and Fellay’s overtures to

A. If I may answer these questions together Rad Trad? As I mentioned earlier it was actually the

$$XP itself that was publishing the Ordo

from 1979 onwards with a considerable number of its clergy using it. When the trustees of the St. Pius V

Association had handed over its assets to the $$PX one of the conditions was

that the pre-Pius XII liturgy was to continue to be used. I understand that one of the original

trustees deeply regrets now not having taken legal action when the $$PX reneged

on the terms. Who knows what might have

been... Anyway, as to the ukase to

enforce the use of the 1962 books this was a consequence of discussions

Lefebvre was having with Rome in the early 1980s. I have letters from both Michael Davies and

Bishop Donald Sanborn – from opposite ends of the Traddieland spectrum - confirming

this to be the case. In his letter

Michael Davies states that the indult Quattuor

abhinc annos was a direct consequence of these discussions. (We can see the

parallels with Summorum Pontificum

and Fellay’s overtures to Rome USA church

of SS Joseph and Padarn in London

Q. Thank

you, Rubricarius, for sending me your Ordo

2015 for review. I have long been an avid reader of the St Lawrence Press

blog and appreciate its efforts to educate the public on the Roman liturgy as

it existed prior to Pius XII and the general process of change. Could you

perhaps tell us more about the specifics of your Ordo, such as the year it follows and how that came about?

A. Thank you, Rad Trad for your interest. The Ordo

began back in the early 1970s as the idea of Fr. Peter J. Morgan (the first

priest ordained by Mgr. Lefebvre for the Fraternity back in 1971). Fr. Morgan soon gathered a sizable group of

interested clergy and somehow managed to create Mass centres almost out of thin

air. He felt it was time to resurrect a traditional Ordo. What must be born in

mind is that the Ordo reflected the

liturgical praxis of what the St. Pius Association (the precursor to the $$PX)

and other traditional clergy were using at the time. Fr. Morgan asked Mr. John Tyson, the compilator emeritus, to produce an Ordo for 1973. John is a truly

exceptional and talented man and could basically think an Ordo in his head for any given year. John’s rather difficult-to-read script – it

looks very like classical Armenian - was patiently deciphered and typed up on

foolscap by the late Miss Penelope Renold and published in three sections by

the ‘St. Pius V Information Centre’. The

first volume. ‘Pars Prima’ was

clearly somewhat rushed with the cover in Miss Renold’s handwriting. ‘Pars

Secunda’ and ‘Pars Semestris’

followed with typed covers. The two following years saw again a simple foolscap

size production but integrated into a single volume. The current format has its origins in the

1976 edition.

The ‘pre-Pius XII’ rubrics were what clergy and their supporters

used at that time. What is now called

the ‘EF’ had, obviously, been used for the couple of years of its existence a

decade earlier – but not by everyone I would add - but no one who was

supporting the cause of ‘Old Rite’ used it in the UK in the 1970s and it did not

make an appearance until a decade later.

Q. Who

were the principle people behind the Ordo

when it began publication under the St Pius V Information Center? What sort of

structure runs the administration of the St Lawrence Press Ordo today?

A. We

have covered this, in part, with the first question. The driving force was Fr. Morgan who

channeled the considerable talents and knowledge of John Tyson. Miss Renold did the typing and, I would

conjecture, the posting to interested parties.

The Ordo was published by the

St. Pius V Association up to and including Ordo

1978. Ordo 1979 was published by the $$PX and they continued to publish

it up to Ordo 1983. All this time Mr. Tyson was continuing to

exercise his considerable talents. Since

2002 the Ordo has been published by

The Saint Lawrence Press Ltd. This is a

legal entity of a company limited by shares in English Law. It has three

directors, including myself, and a company secretary.

Q. How

did the St Lawrence Press survive the liturgical about-face of 1983, when the

Society of St Pius X reversed its 1977 decision

to allow celebrants of the old rite to continue their established custom and

imposed the 1962 liturgy on all priests in the Fraternity? Why

was the pre-Pius XII rite worth saving, from the perspective of those who

continued the St Lawrence Press at the time?

A. If I may answer these questions together Rad Trad? As I mentioned earlier it was actually the

$$XP itself that was publishing the Ordo

from 1979 onwards with a considerable number of its clergy using it. When the trustees of the St. Pius V

Association had handed over its assets to the $$PX one of the conditions was

that the pre-Pius XII liturgy was to continue to be used. I understand that one of the original

trustees deeply regrets now not having taken legal action when the $$PX reneged

on the terms. Who knows what might have

been... Anyway, as to the ukase to

enforce the use of the 1962 books this was a consequence of discussions

Lefebvre was having with Rome in the early 1980s. I have letters from both Michael Davies and

Bishop Donald Sanborn – from opposite ends of the Traddieland spectrum - confirming

this to be the case. In his letter

Michael Davies states that the indult Quattuor

abhinc annos was a direct consequence of these discussions. (We can see the

parallels with Summorum Pontificum

and Fellay’s overtures to

A. If I may answer these questions together Rad Trad? As I mentioned earlier it was actually the

$$XP itself that was publishing the Ordo

from 1979 onwards with a considerable number of its clergy using it. When the trustees of the St. Pius V

Association had handed over its assets to the $$PX one of the conditions was

that the pre-Pius XII liturgy was to continue to be used. I understand that one of the original

trustees deeply regrets now not having taken legal action when the $$PX reneged

on the terms. Who knows what might have

been... Anyway, as to the ukase to

enforce the use of the 1962 books this was a consequence of discussions

Lefebvre was having with Rome in the early 1980s. I have letters from both Michael Davies and

Bishop Donald Sanborn – from opposite ends of the Traddieland spectrum - confirming

this to be the case. In his letter

Michael Davies states that the indult Quattuor

abhinc annos was a direct consequence of these discussions. (We can see the

parallels with Summorum Pontificum

and Fellay’s overtures to

Anyway,

Fr. Black realised that he could no longer produce the Ordo so he asked two dear friends of mine, now my fellow directors,

to produce the Ordo. This decision was made immediately after

Lefebvre left London England

This

did cause some upset with customers so 1985 had an absolutely plain cover.

The

artist Gavin Stamp was a university friend of Mr. Warwick and drew the cover

image for Ordo 1986. Yours truly came across the $$PX in 1988 and

became instantly fascinated by the Ordo. Despite what had happened five years earlier

the majority of clergy were still using ‘pre-Pius XII’ then. I recall a whole year of Sunday’s without a

hint of 1962 – happy days. The current UK

As

to why it was worth saving I think that is because it was the best thing

available at the time and within living memory of so many involved. A great many people identified this as ‘Old

Rite’ as it was what they had experienced before the changes. What I did notice was that many people I met

who were supporting the $$PX had been servers or singers at Fr. Clement

Russell’s church at Sudbury

Q. How

did the 1983 decision and the 1984 indult influence celebrations of the

pre-Vatican liturgy among traditionalists? What sorts of groups, other than

sedevacantists, continued the old rite?

A. A

very interesting question. Again, what I

think needs to be emphasized is that in the early days 1962 was not being used.

Indeed, a very good friend of mine was close friends with an elderly priest

from the NW of England twenty years ago.

The elderly priest told my friend that he and a group of other parish priests just

quietly refused to adopt the new Holy Week.

“We thought Pius had flipped” he told my friend and that ‘normal’

service would be resumed after Pius’ death.

The Old Rite though never entirely died out in England

Q. Please

explain, how you became involved with the Ordo?

A. When I first

discovered the ‘old rite’ in 1987 I found it all very confusing as celebrations

I attended did not match the ‘Saint Andrew’s Daily Missal’ I had. When I first met Mgr. Gilbey his Masses matched

it perfectly so that set me thinking. I

first attended $$PX Masses in 1988 and soon discovered the Ordo. I found it fascinating as at the same time I

was being instructed by a friend, now sadly departed, to learn the

Breviary. I knew John Tyson of course

and remember asking him about (I V) in the Ordo. I said to him ‘John, I think I have worked

out commemorations except the hymn element.

What do you do if the hymn does not have five verses?’ John gave one of his famous chuckles and said

‘You fool, you Tom fool, it is not one to five but of first Vespers.’ Anyway I soon became involved with proof

reading the Ordo. It was all relatively

primitive in those days. Although we have moved on from typing the thing it was

being produced in WordPerfect which was not a WYSIWYG software programme. The symbols for holy days and days of

devotion were drawn in by hand before the pages went off to the printers. Then came along Word2 and Word6 and

subsequent editions by Mr.Gates and it became much easier. Eventually, and I do not recall exactly when,

sometime in the mid-1990s yours truly was producing the scripts and then took

over completely with the Saint Lawrence Press Ltd.

Q. Who

are some past or present customers of the St Lawrence Press that our readers today would recognize?

A. Customer details are covered by legislation such as the Data

Protection Act, notwithstanding basic morality, and so cannot be revealed

without the person’s express consent.

However, a wide range of people from all continents form the current

customer base with the majority of customers coming from the United States and from France

Q. Personally,

I find the Roman rite from 1911-1955 far more complicated in rubrics and

kalendar than what preceded or succeeded it. How do you deal with the

challenges of the Divino Afflatu

system?

A. It certainly made the rubrics of the Roman rite far more

complicated than they were. Indeed, if I

were into conspiracy theories – which I am not - I think one could be forgiven

for thinking it was a deliberate ploy to make life so complicated that any

reform would be received with open arms.

My view is that in reality the reform was rushed through and its

ramifications only began to be understood in the years that followed. Clarifications and differing interpretations

were appearing in Ephemerides Liturgicae

throughout the 1920s and 1930s. Looking

at extant Ordines of the period it is

interesting – to compilers of Ordines

at least – to see the lack of consistency in interpretation. A good example was a few years ago when the

feasts of St. George, St. Mark and SS Philip and James had to be transferred

out of the Paschal Octave. I consulted

four Ordines from 1943, two in my

collection and two in the British Library.

None had exactly the same solution: three were similar but one was way

off. After carefully considering the

rubrics I decided none were actually correct.

To those of us with an interest in such matters it was an amusing study

but life should not be that complex. As

to ‘dealing’ with the system I am afraid that exposure to the ‘Pius X’ rubrics

was part of my formative period so I can think the system in my sleep. Indeed, when I first looked at pre-1911

praxis I found it very hard and it required a lot of effort to understand it,

but I did persevere. It is far superior

in my view but we are limited by the lack of availability of books at the

moment to promote a serious restoration.

Q. Have

you noticed any change in your clientele or in business to the St Lawrence

Press since Summorum Pontificum in

2007? If so, why?

A. There was an

initial flurry of interest and indeed I recall one cleric asking if we would

now adopt the 1962 rubrics. Needless to

say the answer was strongly in the negative.

What is noticeable is that those with a more serious interest in liturgy

see through 1962 quite quickly and look to move to something more

traditional. There is a steadily

increasing number of customers – which is much needed because many of the

original customers have now passed over to Eternity. I think that, ultimately, Summorum Pontificum will be seen as

something that had a damaging effect on the liturgy but the influence of which

faded over time. Indeed, I expect that Summorum Pontificum will be negated by legislation from Rome

Q. In

what direction do you see the future of the old rite headed?

A. After the

period of specious interest following Summorum Pontificum, and I think we really have seen the A

to Z of specious interest, I see a period of contraction and confusion – as we

see today – that will be followed by an implosion. I take the view that there will be a more

real discovery of liturgical orthopraxis and patrimony but that will take time,

a couple of decades at least. I also

believe we will see structural change too – rather like what you have alluded

to in some of your posts mentioning the Minster system for instance. I believe that reform – in a good sense –

will be from grass roots upwards, not from the top down.

Q. In

what sort of research does the St Lawrence Press engage?

A. My own research

interests are the reform of the Roman rite 1903 – 1963; the reform of the Roman

typical editions of the liturgical books from 1568 to 1634, the celebration of

Holy Week, liturgical theology in general and the psychology of religion.

Q. Given

that the early traditionalists and the St. Lawrence Press stopped at 1939, what

would you say in the liturgical legacy of the pope elected that year, Pius XII?

A. I don’t think

the proto-traditionalists thought it terms of 1939 per se but of ‘pre-Pius XII’

As we know men like Evelyn Waugh were totally disparaging about the

Pacelli pontificate. Sadly, what we have

seen over the last quarter of a century or so is the development of what a

blogger friend of mine termed cognitive dissonance. There is a steadfast refusal to acknowledge

the well document facts of the damage done to the Roman liturgy by Pius

XII. In my own view he as much a showman

and narcissist as John Paul II. The

inversion of the axiom lex orandi, lex

credendi was an unmitigated disaster and a charter for the modernists.

Q. Some

insist that the Pauline liturgical changes assimilated new doctrines and that,

by contrast, the Pacellian novelties and reductions are tame, unworthy of

attention in the quest to restore the Roman liturgy. Your thoughts?

A. Well, we have

seen the development of a fallacious revisionism whereby any reform before the

Second Vatican Council is magically ignored and excised from memory. I recall

many years ago that when I came across photographs of Mass versus populum from the 1940s and 1950s my fellow ‘Traddies’ far

from being interested hated me for showing them. There is the creation of a false construct by

these people, they loathe Paul VI but adore old Pacelli. There are the old canards about a) the

differences between 1962 and earlier edition being ‘minor’ and b) the radical

nature of Paul VI’s 1970 changes. With

respect to the first point if the changes are so minor, so trivial, not to be

of any significance or not to be notice then why not just use pre-1962 anyway? Of course, the reality is very different and

the whole point is that the 1962 brigade want to feel superior to everyone else

and use legalism as a weapon against everyone else. As the second point that argument is wildly

over made. What was Mass like the day

before Paul VI’s Missal became law?

People, very conveniently forget, that the 1962MR had not been used for

almost a decade but the 1967 rite with the new Anaphorae, with various lectionaries and, of course, the vernacular

and the fashion of versus populum.

We

appreciate your time, Rubricarius, and thank you again for the opportunity to

review you Ordo for the impending

liturgical year. I speak for my readers in wishing you and the St Lawrence Press the best

in your efforts to preserve the old rite and commending our prayers for that

same intention.